n <- 27

x <- 11

p_seq <- seq(0, 1, length.out = 200)

likelihood <- dbinom(x, n, p_seq)

plot <- ggplot(

data.frame(p = p_seq, likelihood = likelihood),

aes(x = p, y = likelihood)

) +

geom_line(linewidth = 1) +

labs(

x = "Probability of Success (p)",

y = "Likelihood",

title = "Binomial Likelihood Function"

) +

geom_vline(

xintercept = x / n,

color = "red",

linetype = "dashed"

) +

theme_light(base_size = 18) +

theme(panel.grid = element_blank())Lecture 01: Introduction and Foundations

PUBH 8878, Statistical Genetics

About the Instructors

Introductions

- Name, Degree, any other ways you like to define yourself (favorite hot dog brand, etc.)

- Current research focus or research interests.

- What you hope to get out of this course.

Course Site

Zotero

Course Logistics and Expectations

Grading Breakdown

| Assignment Type | % of Grade |

|---|---|

| Problem Sets | 60% |

| Class Participation | 20% |

| Research Project | 20% |

Total Workload: 112.5 hours (5+ hrs/week independent + 6 hrs/week class/async)

Problem Sets (60% of grade)

- Weekly assignments blending mathematical derivations with coding

- Collaborative time provided in class

- Individual work required – substantial time outside class

- Late penalty: 1% per hour (first 5 hours), then 5% per day

- Format: Mix of theory problems and R/Bioconductor analysis

Class Participation (20% of grade)

More than just showing up!

- Come prepared with questions from async materials

- Engage thoughtfully in discussions and problem-solving

- Demonstrate mastery through insightful contributions

- Collaborate respectfully - help others understand concepts

Quantitative + Qualitative Assessment: Async responses + live session engagement

Research Project (20% of grade)

Final third of semester - Choose your own adventure!

Project Types

- Computational methods

- Applied analysis

- Methodological development

- All based on primary literature

Deliverables

- Scientific paper (Genetics journal format)

- Conference-style presentation

- Groups of up to 3 encouraged

- Individual contributions must be clear

Course Structure Overview

Foundation → Scale → Specialization (10 weeks)

- Weeks 1-4: Foundations (Mendelian genetics, heritability, likelihood algorithms, population structure & Bayesian methods)

- Week 5: GWAS at scale (design, linear mixed models, meta-analysis)

- Weeks 6-7: Prediction models & multiple testing control

- Weeks 8-9: Binary traits & causal inference (Mendelian randomization)

- Week 10: Advanced AI topics in statistical genetics

Lab Component: Hands-on R/Bioconductor workflows parallel to lectures

Technology Setup Requirements

- R (4.5+) and IDE installation

- Git setup and basic commands

- Zotero for reference management

- Zoom

- Optional: HPC access

Course Textbook

Sorensen (2025)

What is statistical genetics?

A statistical geneticist may want to know

- Is there a genetic component contributing to the total variance of these traits?

- Is the genetic component of the traits driven by a few genes located on a particular chromosome, or are there many genes scattered across many chromosomes? How many genes are involved and is this a scientifically sensible question?

- Are the genes detected protein-coding genes, or are there also noncoding genes involved in gene regulation?

- How is the strength of the signals captured in a statistical analysis related to the two types of genes? What fraction of the total genetic variation is allocated to both types of genes?

- What are the frequencies of the genes in the sample? Are the frequencies associated with the magnitude of their effects on the traits?

- What is the mode of action of the genes?

A statistical geneticist may want to know

- What proportion of the genetic variance estimated in 1 can be explained by the discovered genes?

- Given the information on the set of genes carried by an individual, will a genetic score constructed before observing the trait help with early diagnosis and prevention?

- How should the predictive ability of the score be measured?

- Are there other non-genetic factors that affect the traits, such as smoking behavior, alcohol consumption, blood pressure measurements, body mass index and level of physical exercise?

- Could the predictive ability of the genetic score be improved by incorporation of these non-genetic sources of information, either additively or considering interactions? What is the relative contribution from the different sources of information?

What does the data look like?

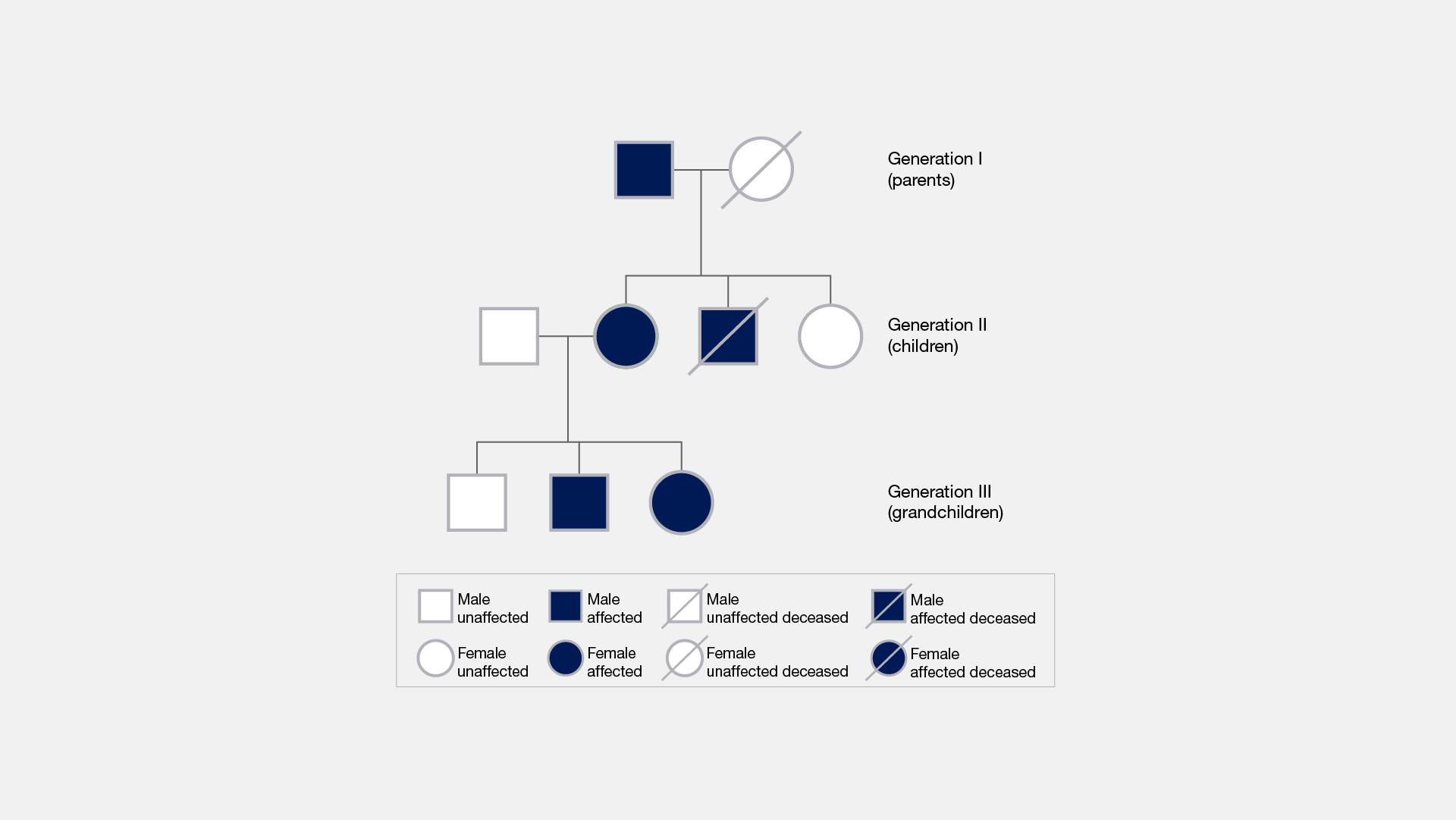

Family/Pedigree Studies

Family/Pedigree Studies

What does the data look like?

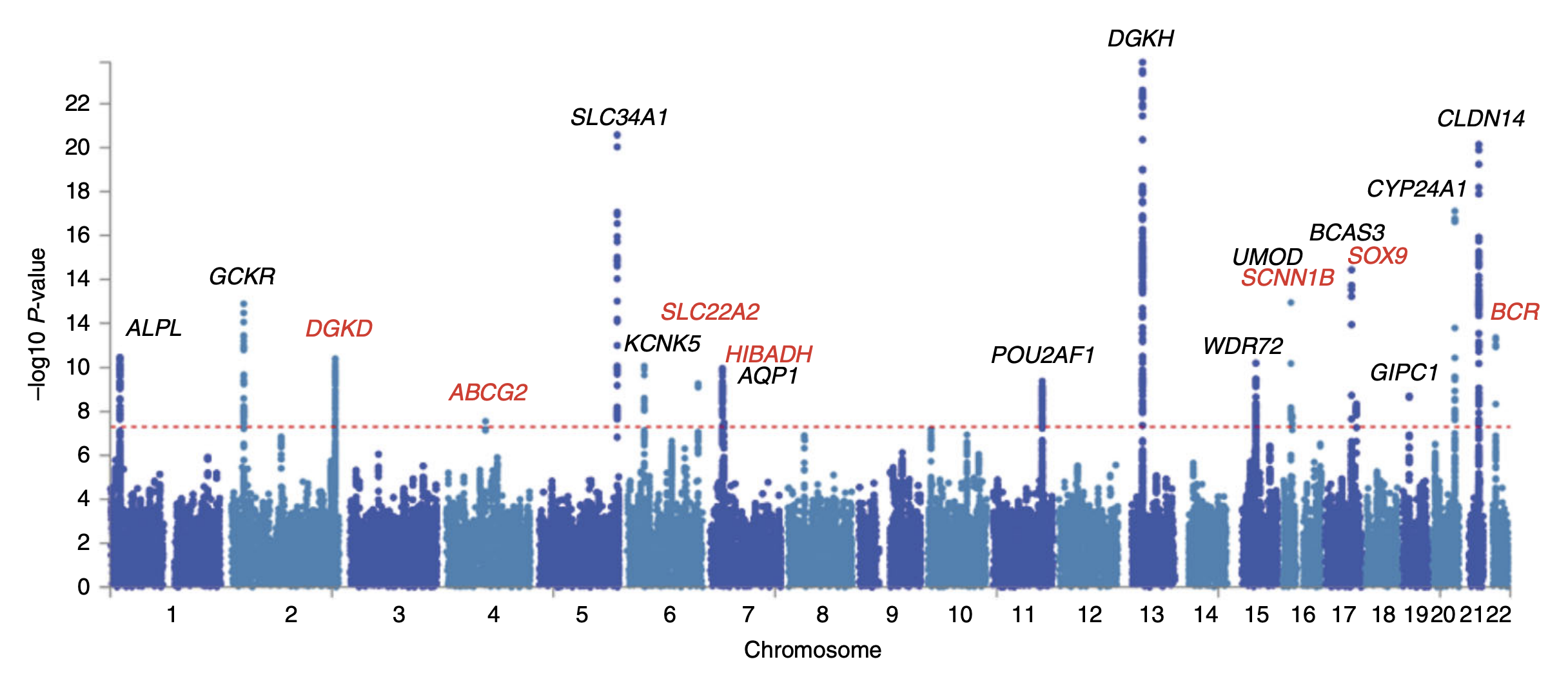

Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS)

Genome-Wide Association Studies

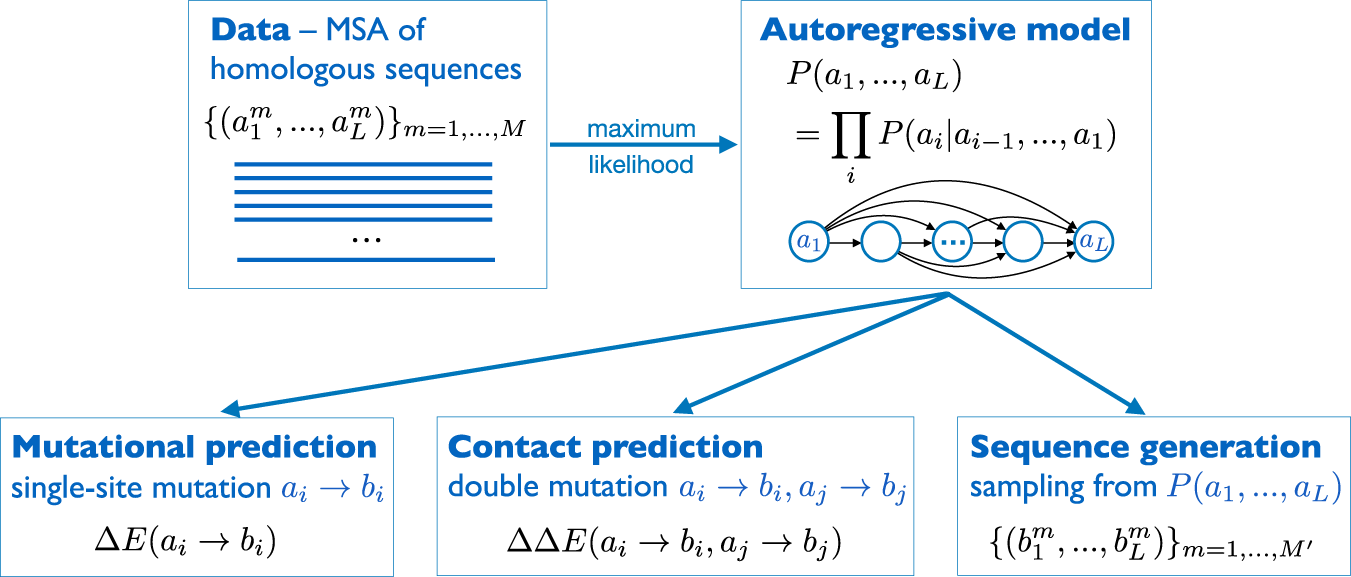

Core abstractions for quantitative biology

- Model-Building

- Formulate generative models linking genotype, environment, and phenotype (e.g., linear mixed, Bayesian hierarchical, non-parametric kernels).

- Encode biological structure: linkage & LD, population stratification, dominance/epistasis, multi-omics priors.

- Balance realism and tractability to enable scalable computation on genome-scale data.

Core abstractions for quantitative biology

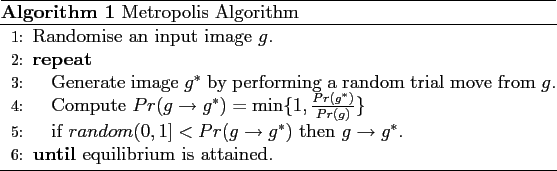

- Inference

- Estimate unknown parameters and latent effects via likelihood maximisation, EM, MCMC, or SGD

- Quantify uncertainty with standard errors, posterior intervals, and credible sets

- Control false discoveries across millions of tests with FDR/Q-value, permutation, and empirical-Bayes shrinkage.

Core abstractions for quantitative biology

- Prediction

- Use fitted models for out-of-sample trait prediction: BLUP/GBLUP, ridge/lasso/elastic-net, Bayesian whole-genome regressions, random forests, neural nets.

- Evaluate accuracy (MSE, AUC), bias–variance trade-off, calibration, and portability across ancestries or cell types.

- Translate genomic predictions into actionable scores for breeding, risk stratification, and drug-target prioritisation.

Core abstractions for quantitative biology

- Interpretation & Validation

- Integrate functional annotations, eQTL, and single-cell data to refine biological mechanisms.

- Perform replication, cross-cohort meta-analysis, and sensitivity analyses to population assumptions.

- Communicate findings with clear visualisations and reproducible workflows (R/Bioconductor, Git, notebooks).

Early work in the field

Genetics, statistics, and eugenics, have always been closely linked

The ethics of genetics and genomics is/(was) of great importance!

Some vocabulary

- Trait/Phenotype: A measurable characteristic of an organism, such as height, weight, or disease status.

- Gene: Unit of inheritance

- Genotype: The genetic constitution of an individual, often represented by specific alleles at particular loci.

- Allele: A variant form of a gene that can exist at a specific locus on a chromosome.

- Locus: A specific, fixed position on a chromosome where a particular gene or genetic marker is located.

- Diploid: Having two sets of chromosomes (one from each parent)

- Penetrance: Likelihood of expressing a phenotype given a genotype

- Polymorphism: The occurrence of two or more genetically determined forms in a population, such as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or copy number variations (CNVs).

- Genetic Marker: A specific DNA sequence with a known location on a chromosome that can be used to identify individuals or species, often used in genetic mapping or association studies.

Some vocabulary

- Mendelian Disease: A disease caused by a mutation in a single gene, following Mendelian inheritance patterns (dominant, recessive, X-linked).

- Linkage Disequilibrium (LD): The non-random association of alleles at different loci, indicating that certain allele combinations occur together more frequently than expected by chance.

- Heritability: The proportion of phenotypic variance in a trait that can be attributed to genetic variance, often estimated through twin or family studies.

- Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS): A study that looks for associations between genetic variants across the genome and specific traits or diseases in a large population.

- Polygenic Score (PGS): A score that aggregates the effects of multiple genetic variants to predict an individual’s genetic predisposition to a trait or disease.

- Quantitative Trait Locus (QTL): A region of the genome that is associated with a quantitative trait, often identified through linkage or association mapping.

- Epistasis: The interaction between genes where the effect of one gene is modified by one or more other genes, influencing the expression of a trait.

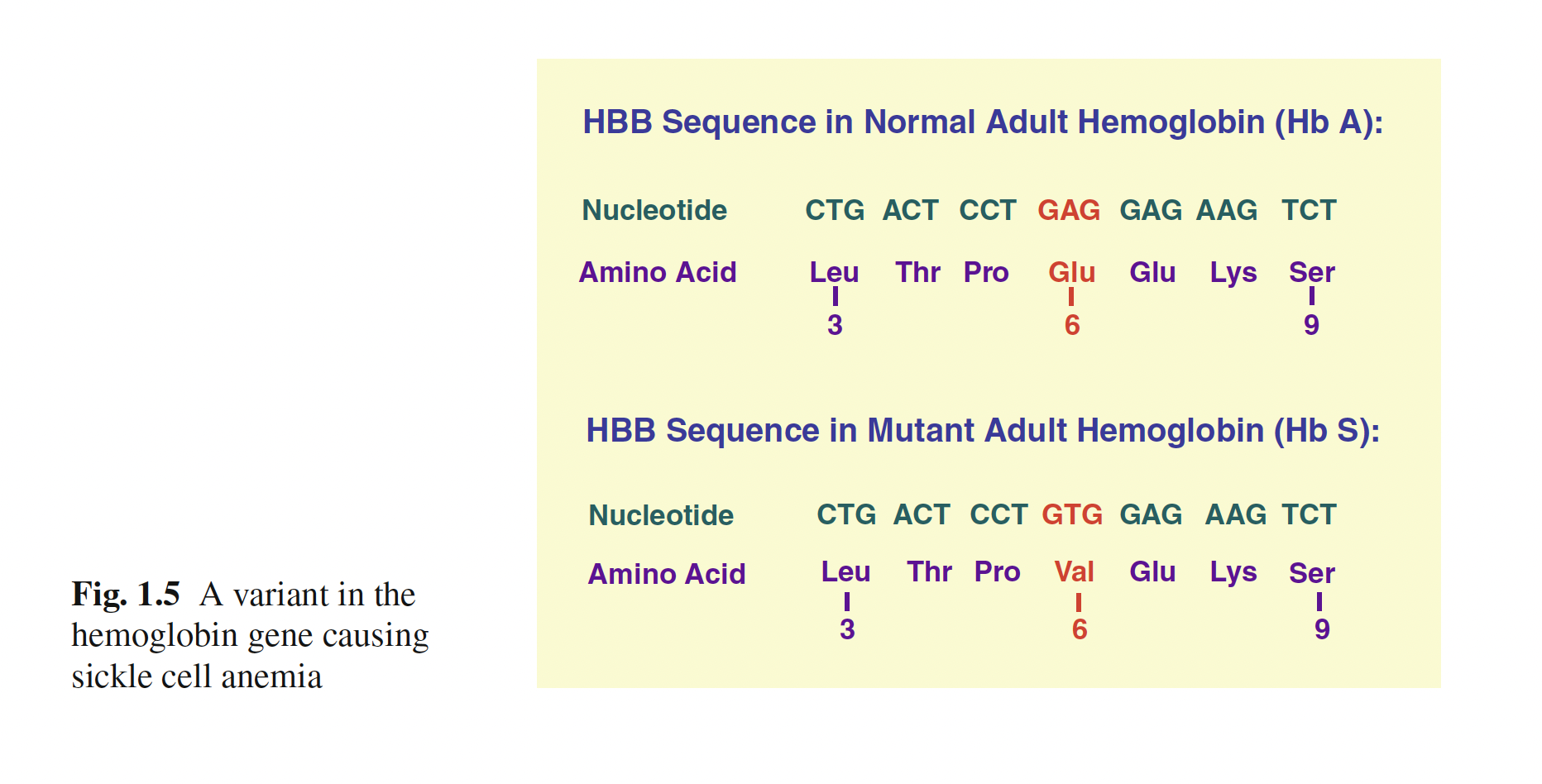

Genetic Variant Example

Laird and Lange (2011)

Probability Refresher

Random Variables and Distributions

- A random variable is a numerical summary of randomness (e.g., the count of (A) alleles in a sample). We will denote random variables with uppercase letters (e.g., X, Y).

- We use a model (e.g., binomial/multinomial) to describe how data vary from sample to sample.

- This is otherwise known as a probability mass function (pmf) for discrete variables, or a probability density function (pdf) for continuous variables

- Key ideas:

- Expectation (mean) and variance: long‑run average and spread.

- E[X] = \sum x \cdot P(X = x) (discrete) or E[X] = \int x f(x) dx (continuous)

- \textsf{Var}(X) = E[(X - E[X])^2] = E[X^2] - (E[X])^2

- Standard error (SE): typical sampling variability of an estimator.

- \textsf{SE} = \frac{\sigma}{\sqrt{n}} (uncertainty in sample estimates)

- Central Limit Theorem (CLT): averages and proportions are roughly normal for large (n).

- \bar{X} \sim N\left(\mu, \frac{\sigma^2}{n}\right) as n \to \infty

- Expectation (mean) and variance: long‑run average and spread.

Probability Distributions vs Sampling Distributions

- A probability distribution describes how a random variable behaves in the population.

- Example: X \sim \textsf{Binomial}(n, p)

- A sampling distribution describes how a statistic (e.g., sample mean, sample proportion) behaves across repeated samples from the population.

- Example: \hat{p} \sim N\left(p, \frac{(p(1-p))}{n}\right) as n \to \infty

Probability Refresher

Key Distributions in Statistical Genetics

Binomial Distribution X \sim \textsf{Binomial}(n, p) P(X = k) = \binom{n}{k} p^k (1-p)^{n-k}

Used for: Allele counts

Normal Distribution X \sim N(\mu, \sigma^2) f(x) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2\pi\sigma^2}} e^{-\frac{(x-\mu)^2}{2\sigma^2}}

Used for: Quantitative traits, effect sizes

Conditional Probability and Independence

- Conditional Probability: P(A|B) = \frac{P(A \cap B)}{P(B)}

- Bayes’ Theorem: P(A|B) = \frac{P(B|A)P(A)}{P(B)}

- Independence: P(A \cap B) = P(A) \cdot P(B) \iff A and B are independent

Conditional probability and Bayes’ Theorem are crucial for understanding rare disease genetics! For example, consider a rare disease with a prevalence of 1 in 10,000. If a genetic test has a sensitivity of 99% and a specificity of 99%, we can use Bayes’ Theorem to calculate the probability that an individual has the disease given a positive test result.

\begin{align*} P(Disease|Positive) &= \frac{P(Positive|Disease)P(Disease)}{P(Positive)} \\ &= \frac{(0.99)(0.0001)}{(0.99)(0.0001) + (0.01)(0.9999)} \\ &\approx 0.0098 \end{align*}

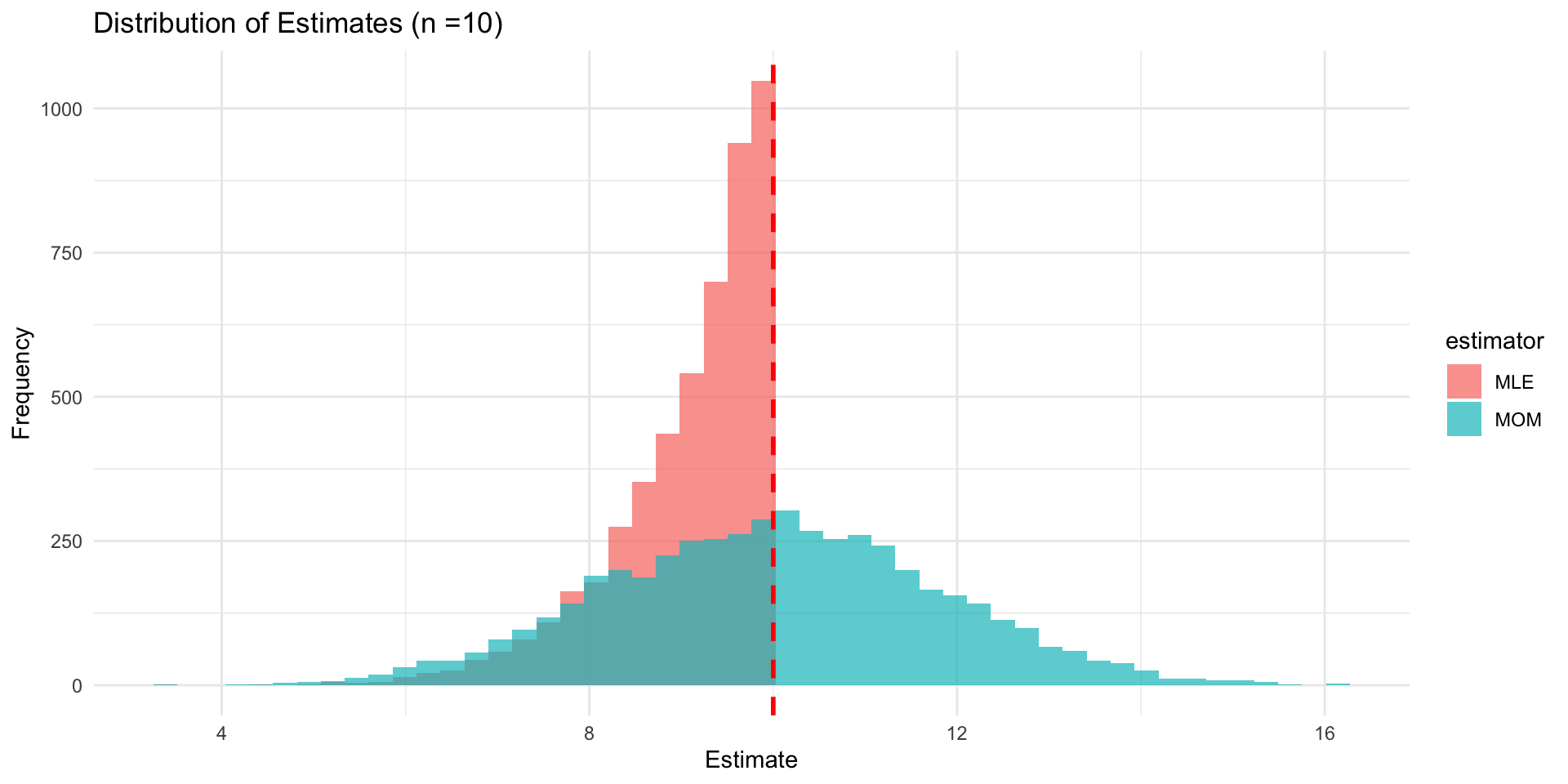

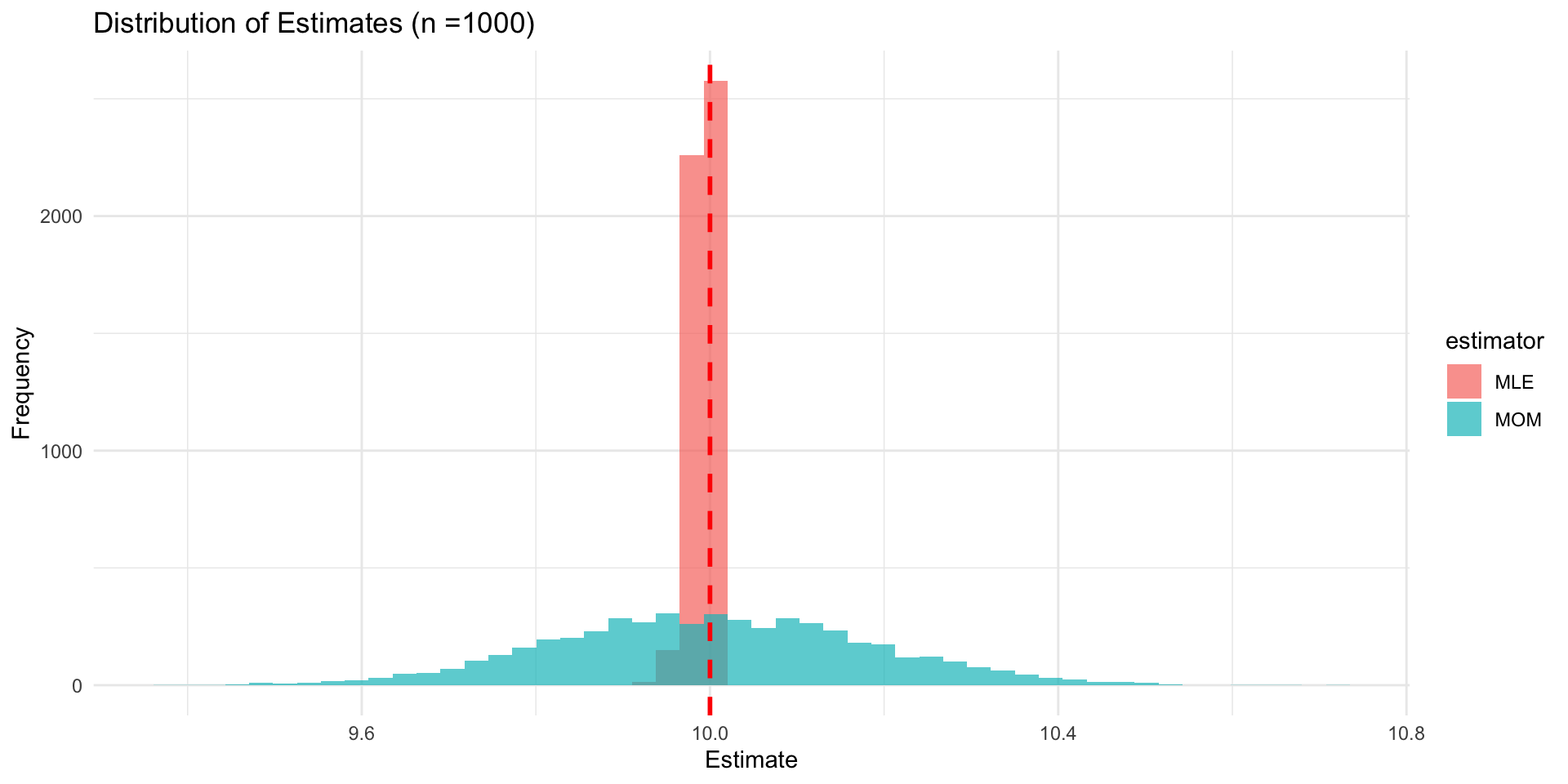

Parameter Estimation

- Imagine a geneticist is studying allele ages (i.e., how many generations ago an allele arose via mutation) under a simplified model where new mutations arise randomly and uniformly over a fixed window — say, the last \theta generations.

- We could model X \sim \textsf{Uniform}(0, \theta).

- We have our observed sample \{x_1,x_2, \ldots, x_n\}, ages in generations of n observed alleles.

- For concreteness, let our sample be \{0, 1, 8, 4, 3, 7, 7, 6\}.

- How should we estimate \theta ?

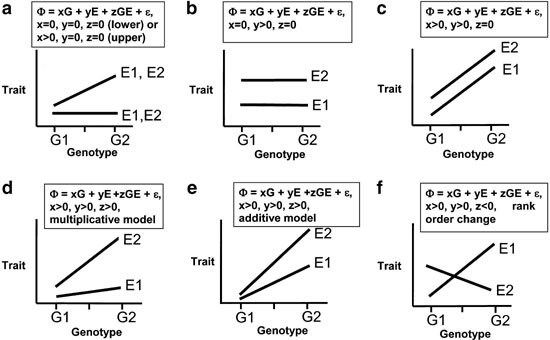

Genetic Models

- Understanding random variables, sampling distributions, and bias/variance of estimators helps motivate biological questions, and understand how they can be answered

- Let y be the expression of a trait, G be the additive contribution of genetic variables, and an environmental value E;

- What assumptions do we make via the following models?

\begin{align} y &= G + E \\ y &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 G + \beta_2 E + \epsilon \\ y &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 G + \beta_2 E + \epsilon, \quad \epsilon \sim N(0, \sigma^2) \\ y &= \beta_0 + \beta_1 G + \beta_2 E + \beta_3 \left(G \times E\right) + \epsilon, \quad \epsilon \sim N(0, \sigma^2) \end{align}

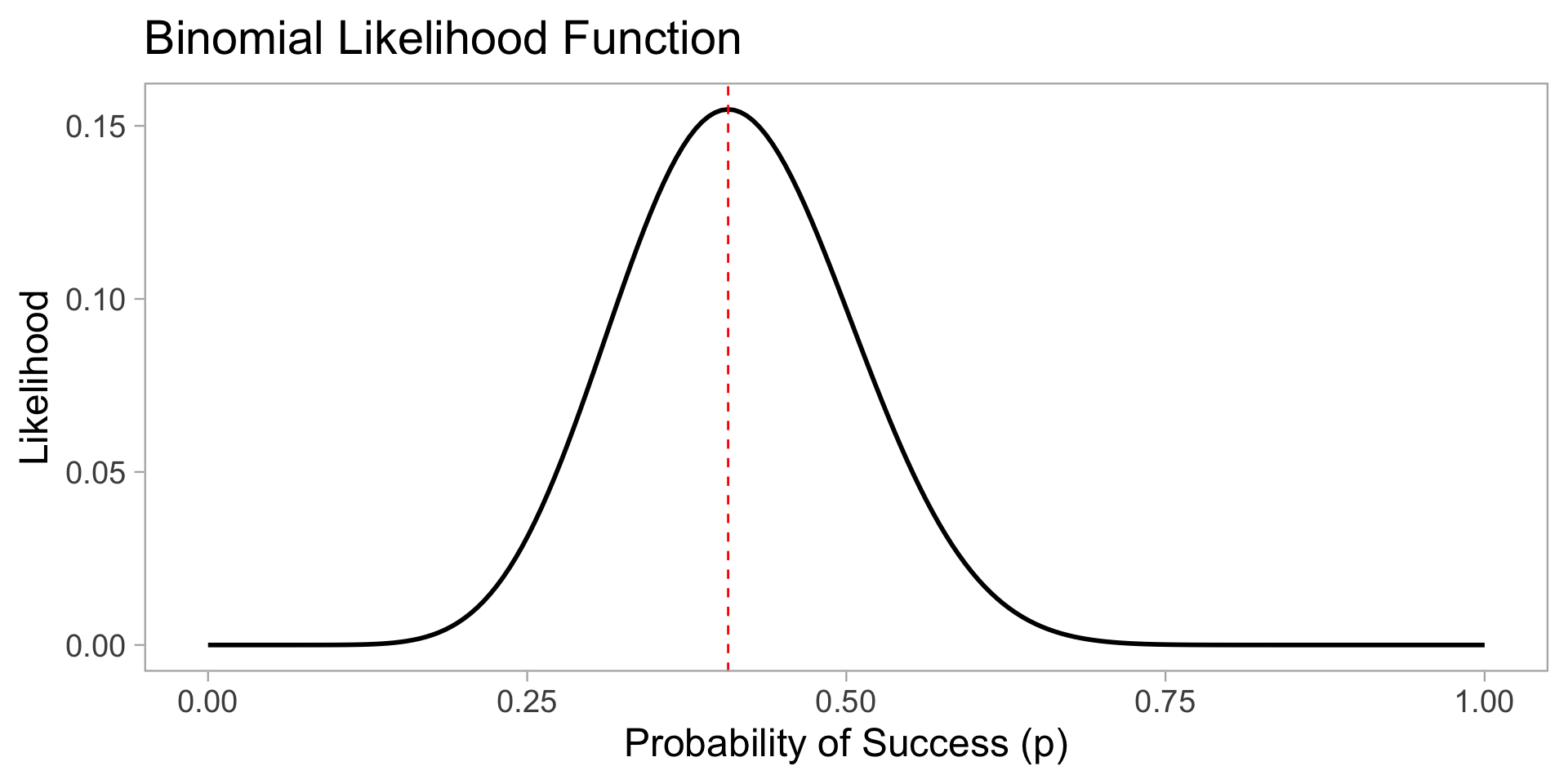

Modeling

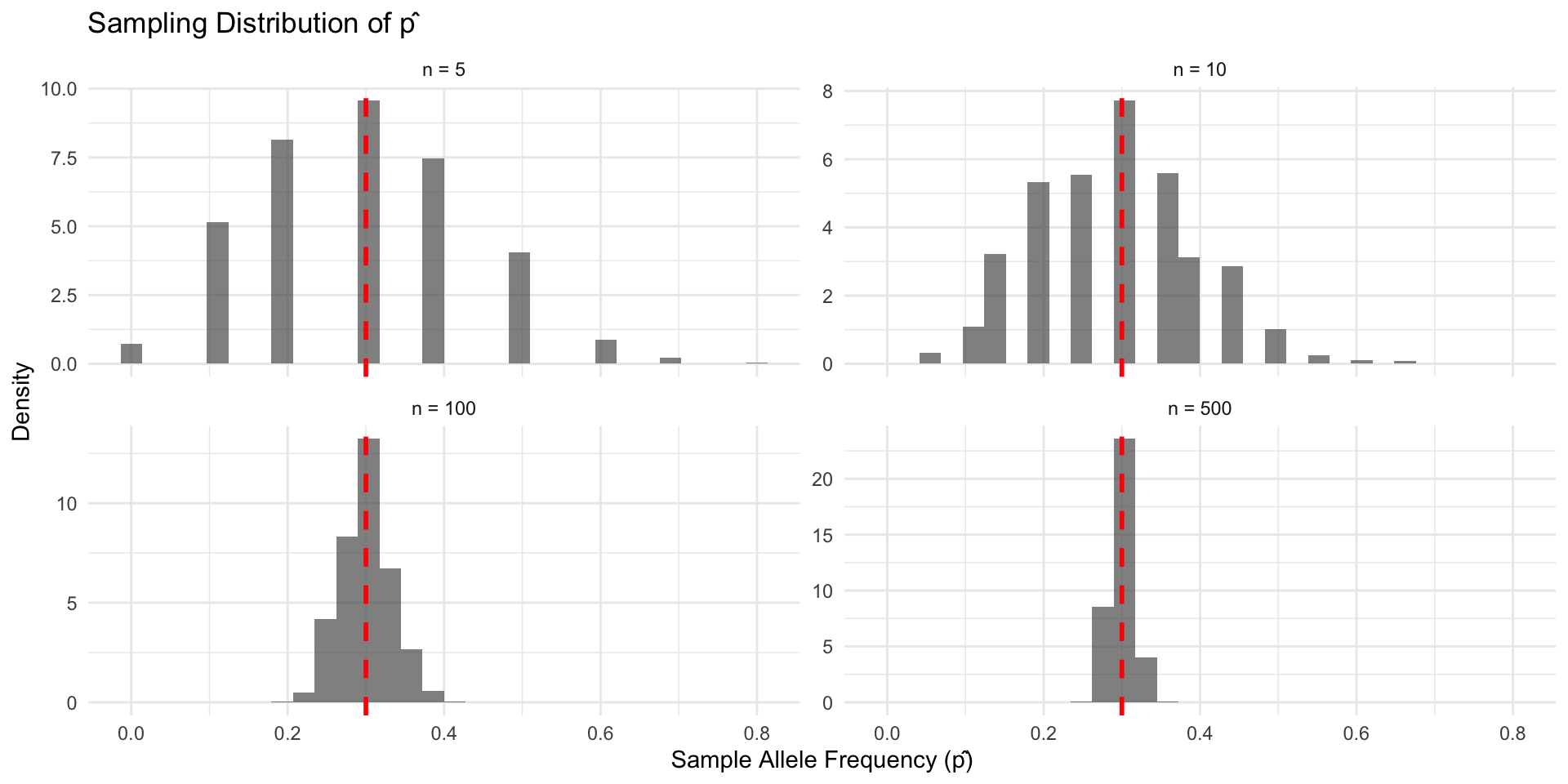

- Imagine that we have a sample size of n unrelated haploid individuals from some population

- We want to estimate allele frequencies for a biallelic SNP, say A/a

- In our sample, we observe x individuals with allele A and n - x individuals with allele a

- Let p be the frequency of allele A and q = 1 - p be the frequency of allele a

Pr(X = x| n, p) = \binom{n}{x} p^x q^{n - x}

- Lets say we observe n = 27 and x = 11. How do we estimate p?

Likelihood Functions

The likelihood function is a function of the parameters of a statistical model, given specific observed data.

It represents the plausibility of different parameter values based on the observed data.

For a given set of data, the likelihood function is defined as: L(\theta | data) = P(data | \theta)

In our case, the likelihood function for p is: L(p | x = 11, n = 27) = P(X = 11 | n = 27, p) = \binom{27}{11} p^{11} (1 - p)^{16}

We are asking, “how likely is it that we would observe this data for different values of p?”

Maximum Likelihood Estimator

Our likelihood function for p is

L(P|x = 11, n = 27) = {27 \choose 11} p^{11} q^{27-11}

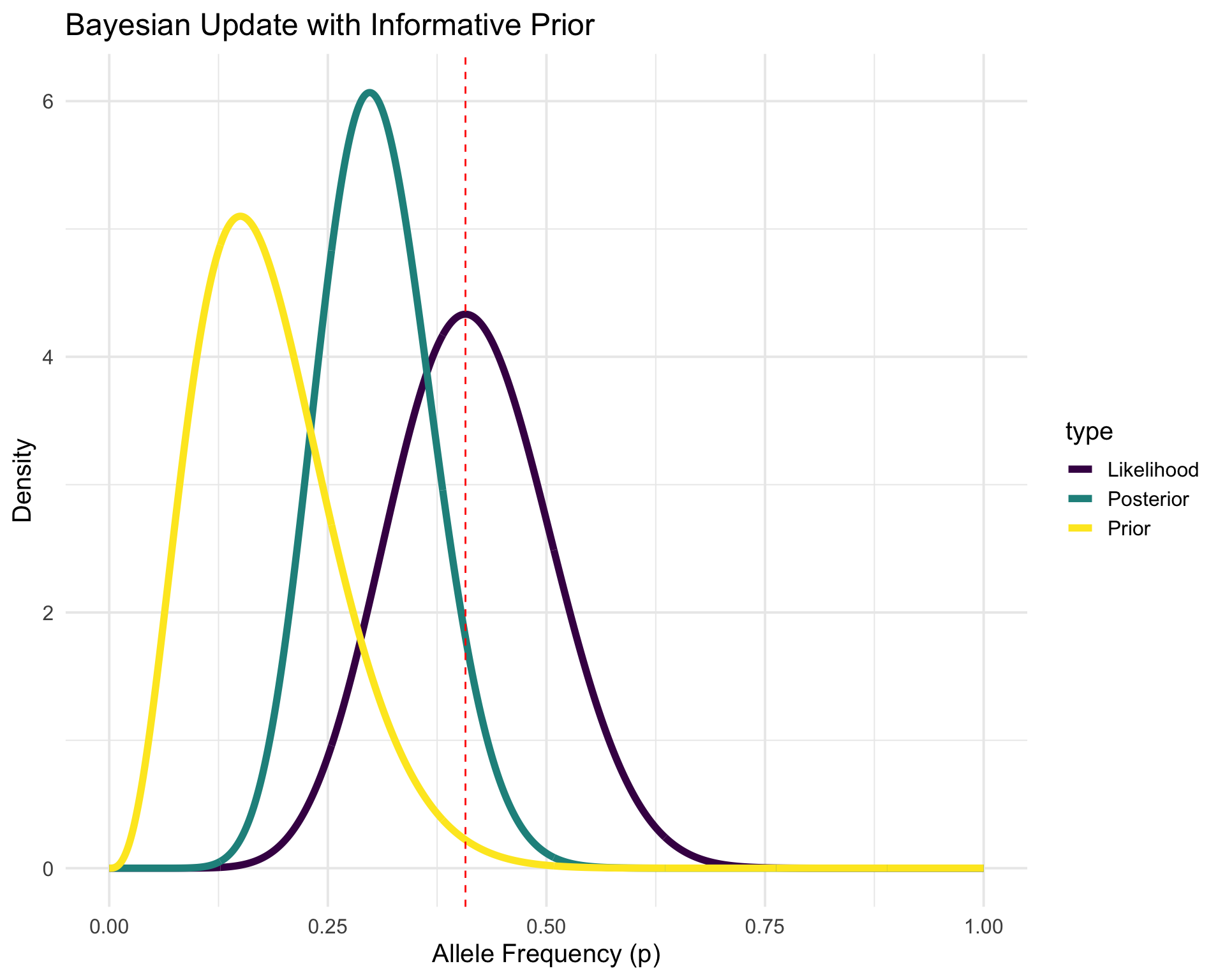

Modeling, but make it bayesian

- In Bayesian statistics, we treat parameters as random variables and use probability distributions to represent our uncertainty about them.

- We start with a prior distribution that reflects our beliefs about the parameter before seeing the data.

- We then use the observed data to update our beliefs and obtain a posterior distribution.

- The posterior distribution combines the information from the prior and the likelihood of the observed data using Bayes’ theorem: P(p | data) = \frac{P(data | p) P(p)}{P(data)}

- Let’s say we have run a previous experiment and observed n = 20 individuals and x = 3 individuals with allele A (again, bilelic SNP).

- We can use this information to inform our prior distribution for p

Modeling, but make it bayesian

p <- seq(0, 1, length.out = 1000)

# Prior (Beta distribution from previous experiment)

prior <- dbeta(p, 3 + 1, 17 + 1)

# Likelihood (Beta distribution from current data)

likelihood <- dbeta(p, 11 + 1, 16 + 1)

# Posterior (Beta distribution combining both)

posterior <- dbeta(p, 14 + 1, 33 + 1)

# Combine into a data frame

plot_data <- data.frame(

p = rep(p, 3),

density = c(prior, likelihood, posterior),

type = rep(c("Prior", "Likelihood", "Posterior"), each = length(p))

)

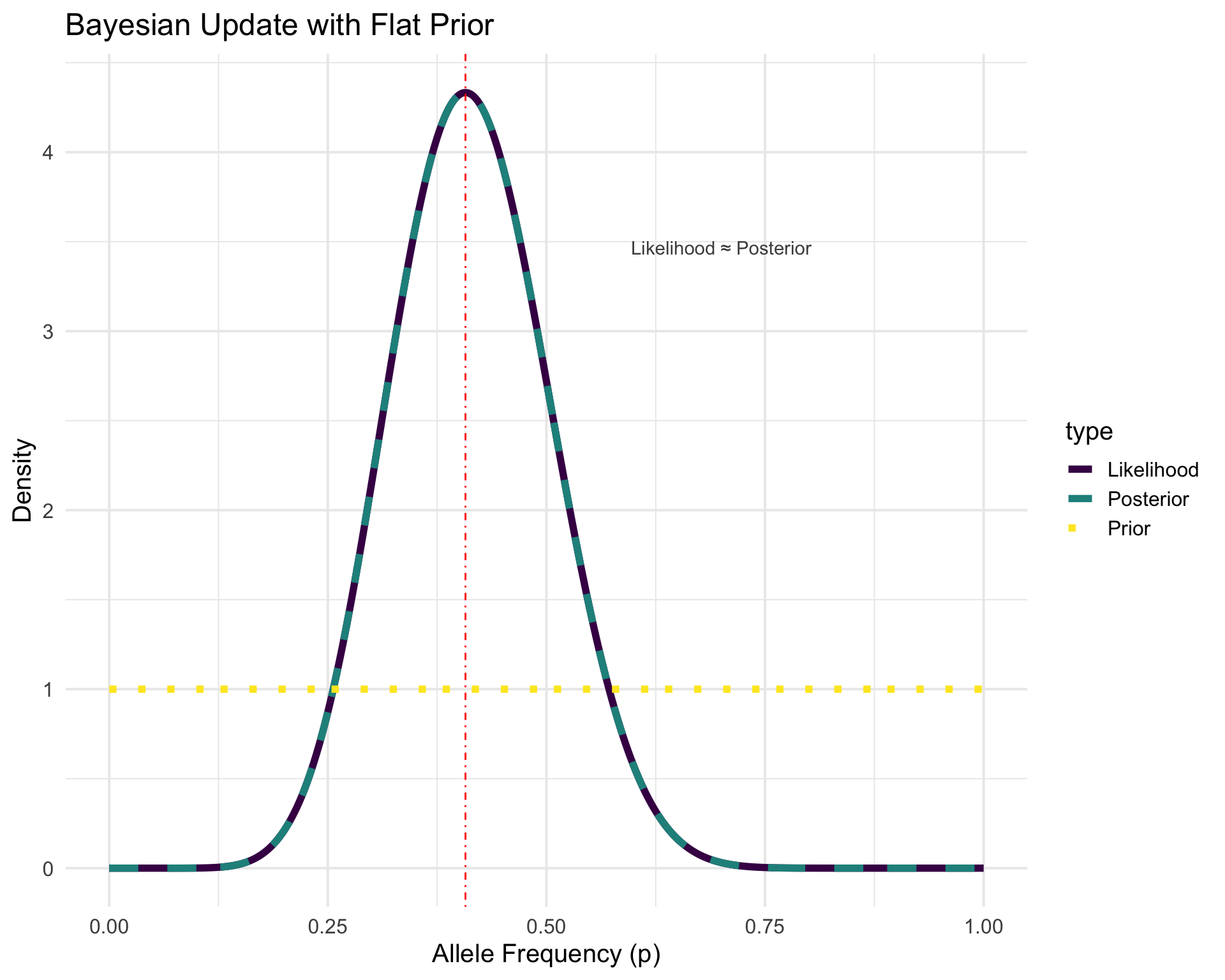

# Add flat prior distribution

flat_prior <- dbeta(p, 1, 1)

flat_posterior <- dbeta(p, 12, 17)

plot_data <- rbind(

plot_data,

data.frame(

p = rep(p, 3),

density = c(flat_prior, likelihood, flat_posterior),

type = rep(c("Prior", "Likelihood", "Posterior"), each = length(p))

)

)

# Add a column to distinguish between informative and flat scenarios

plot_data$scenario <- c(rep("Informative", 3000), rep("Flat", 3000))p1 <- ggplot(

plot_data %>% filter(scenario == "Informative"),

aes(x = p, y = density, color = type)

) +

geom_line(linewidth = 2) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 11 / 27, linetype = "dashed", color = "red") +

labs(

x = "Allele Frequency (p)",

y = "Density",

title = "Bayesian Update with Informative Prior"

) +

scale_color_viridis_d() +

theme_minimal(base_size = 15)p2 <- ggplot(

plot_data %>% filter(scenario == "Flat"),

aes(x = p, y = density, color = type, linetype = type)

) +

geom_line(linewidth = 2) +

scale_linetype_manual(values = c("Prior" = "dotted", "Likelihood" = "solid", "Posterior" = "dashed")) +

geom_vline(xintercept = 11 / 27, linetype = "dotdash", color = "red") +

labs(

x = "Allele Frequency (p)",

y = "Density",

title = "Bayesian Update with Flat Prior"

) +

theme_minimal(base_size = 15) +

scale_color_viridis_d() +

annotate("text",

x = 0.7, y = max(flat_posterior) * 0.8,

label = "Likelihood ≈ Posterior", color = "gray30"

)

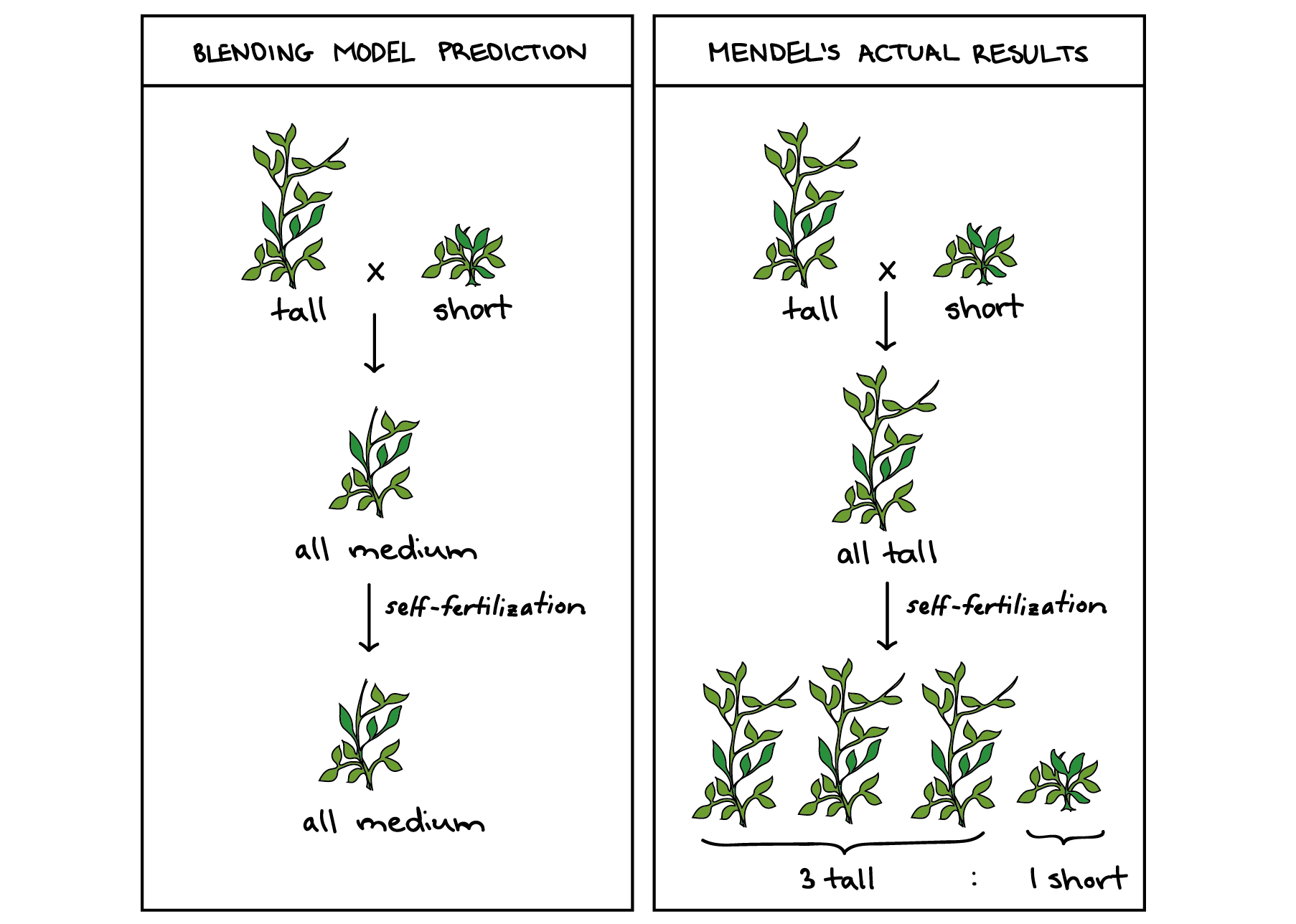

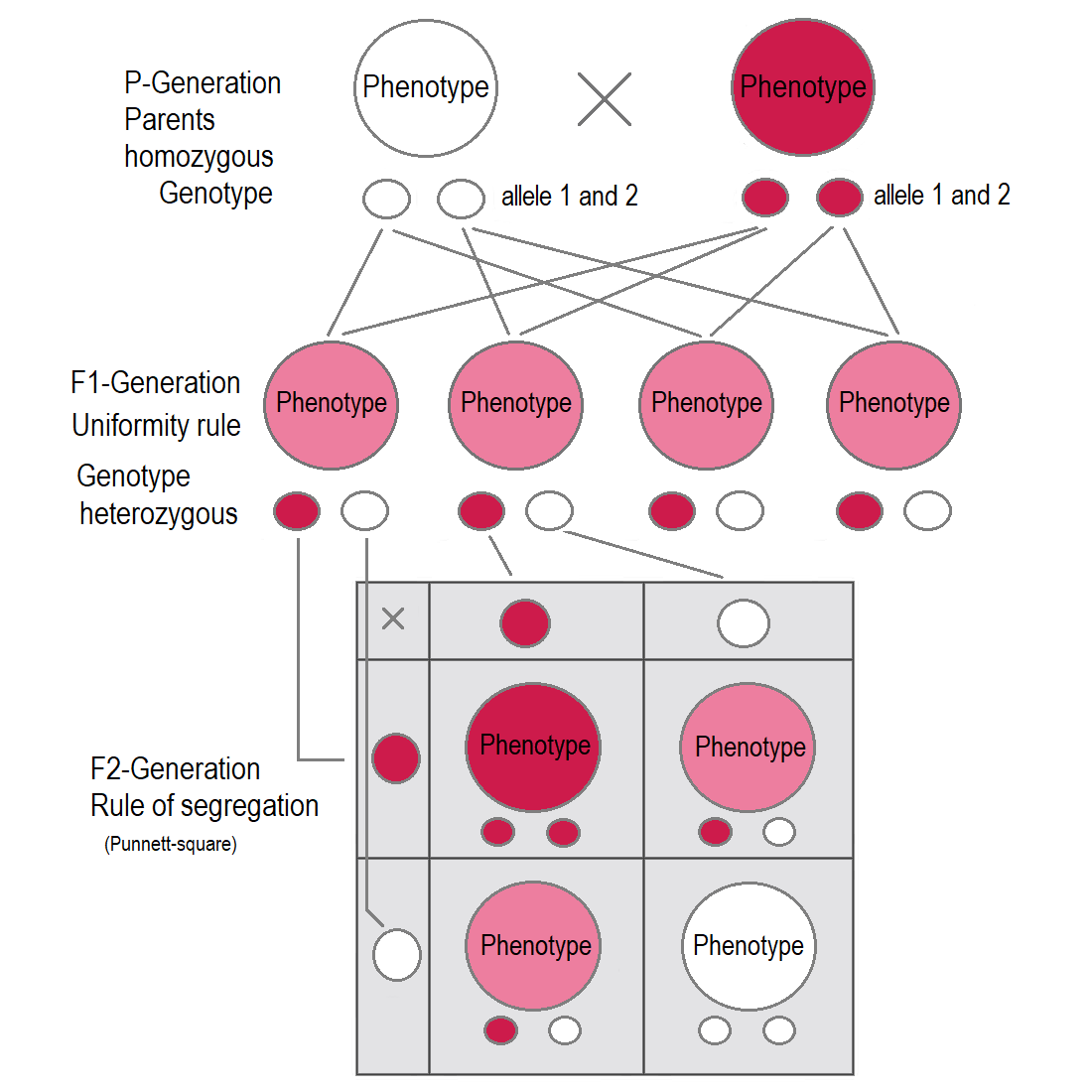

Mendel’s Laws

Mendel’s First Law (Segregation)

One allele of each parent is randomly transmitted, with probability 1/2, to the offspring; the alleles unite randomly to form the offspring’s genotype.

Mendel’s Second Law (Independent Assortment)

At different loci, alleles are transmitted independently (when loci are unlinked).

Worked Example: Segregation (3:1 Ratio)

Cross: Aa × Aa

Punnett Square

| A | a | |

|---|---|---|

| A | AA | Aa |

| a | Aa | aa |

Expected Ratios

- Genotypic: 1 AA : 2 Aa : 1 aa

- Phenotypic: 3 dominant : 1 recessive

- Probabilities: P(AA)=\frac14, P(Aa)=\frac12, P(aa)=\frac14

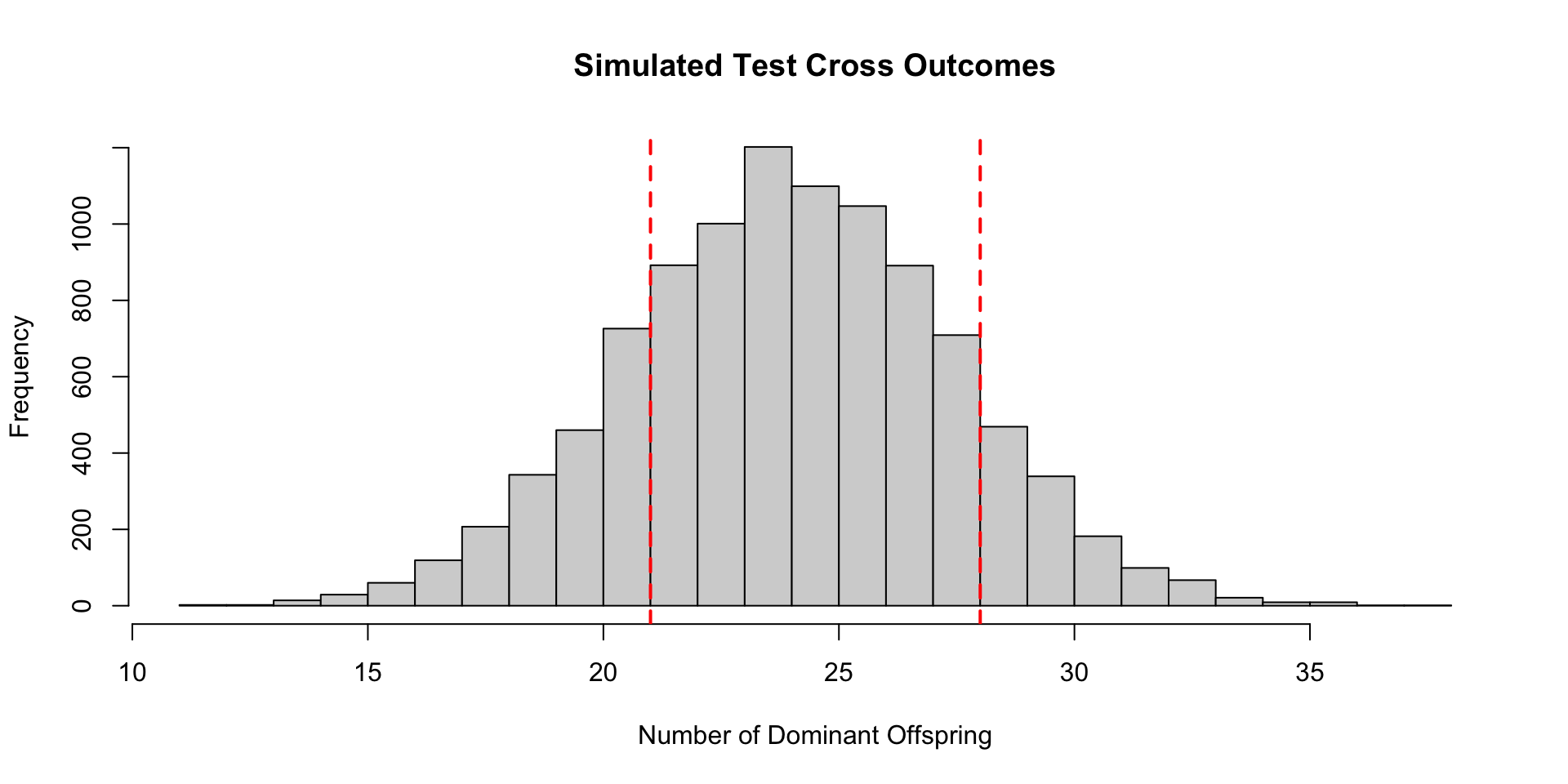

Test Cross Example

Proving law of segregation with a test cross

Example data:

- Cross: Aa × aa

- Observed: 21 dominant, 28 recessive

- Null hypothesis: Probability of transmission is 1:1.

- Alternative hypothesis: Probability of transmission is not 1:1.

- How to test this?

Our question is related to observation of proportions –> use a chi-squared goodness-of-fit test or a binomial test.

Test Cross Example

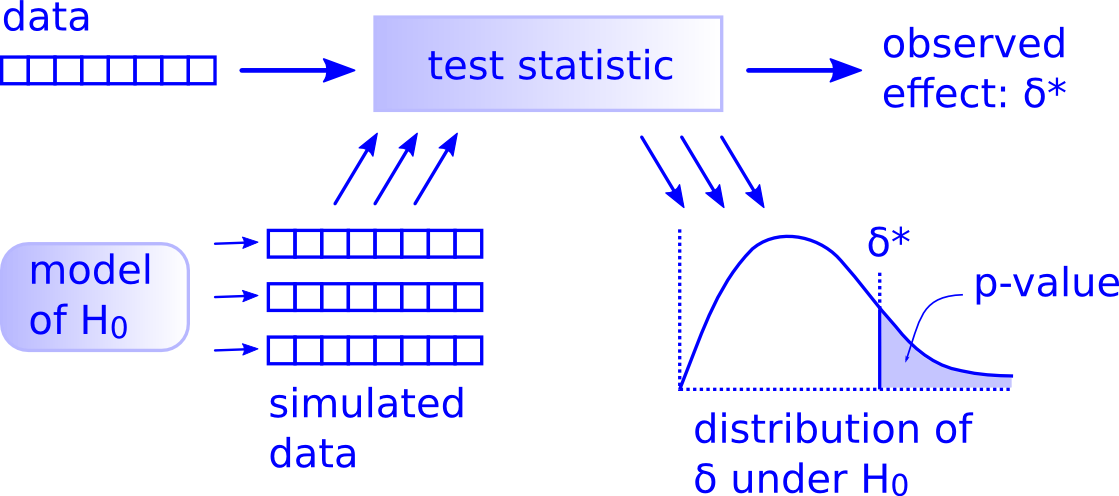

Testing via Simulation

We could also simulate our idea of the null hypothesis to get a sense of how extreme our observed data is.

[1] 0.3868

On Simulations

Downey (2015)

Estimation of Allele Frequencies

n_{AA} = Number of individuals with genotype AA n_{Aa} = Number of individuals with genotype Aa n_{aa} = Number of individuals with genotype aa

where, n = n_{AA} + n_{Aa} + n_{aa} = N.

The sample proportions of allele A is:

\hat{p} = \frac{2n_{AA} + n_{Aa}}{2n}

The usual standard error for a proportion is \sqrt{\hat{p}(1 - \hat{p})/2n}, but this assumes independence of the 2n sampled chromosomes.

Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE): Assumptions

Let’s reframe the problem in terms of genotype frequencies. First, some assumptions:

- Random mating

- Large population (no strong drift in one generation)

- No selection, no migration, no mutation (in the generation under study)

- Accurate genotypes (no systematic genotyping error)

If these hold, and the allele frequency of A is p (so q = 1-p), we say that the population is in Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE). The population genotype probabilities are:

P(AA)=p^2 \quad P(Aa)=2pq \quad P(aa)=q^2

As a consequence, the genotype frequencies in a random sample of n individuals are approximately multinomially distributed with cell probabilities (p^2, 2pq, q^2). Thus, the sampling error of \hat{p} is approximately \sqrt{p(1-p)/2n}.

This confidence interval is known as a Wald confidence interval.

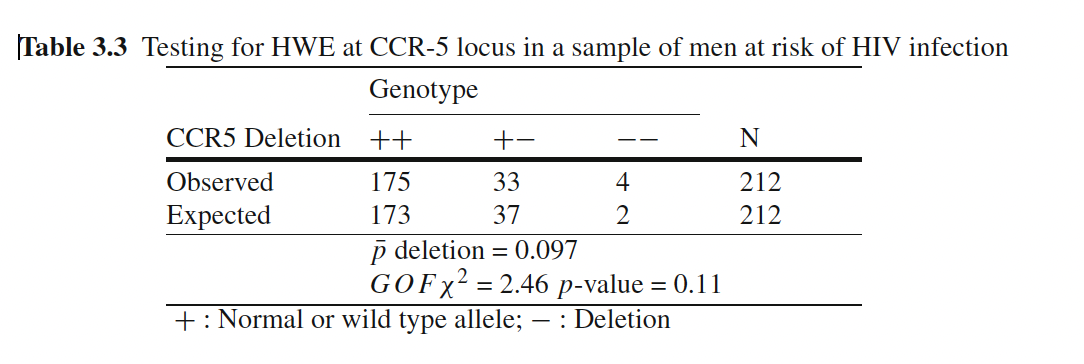

Testing for HWE

- With large samples, we can test for HWE using a chi-squared goodness-of-fit test.

Laird and Lange (2011)

HWE: Worked Example

[1] 0.9033019[1] 172.982311 37.035377 1.982311[1] 0.1126299HWE in Practice

- HWE is a useful null model for quality control of genotype data.

- Deviations from HWE can indicate genotyping errors, population stratification, or selection

Sampling distributions: intuition via simulation

set.seed(123)

true_p <- 0.3

sample_sizes <- c(5, 10, 100, 500)

n_sims <- 1000

sampling_results <- map_dfr(sample_sizes, function(n) {

p_hats <- replicate(n_sims, {

# Sample n individuals (2n alleles total)

alleles <- rbinom(n, 2, true_p) # each individual contributes 0,1,2 A alleles

sum(alleles) / (2 * n) # sample allele frequency

})

tibble(sample_size = n, p_hat = p_hats,

theoretical_se = sqrt(true_p * (1 - true_p) / (2 * n)))

})Sampling distributions: intuition via simulation

# Plot sampling distributions

ggplot(sampling_results, aes(x = p_hat)) +

geom_histogram(aes(y = after_stat(density)), bins = 30, alpha = 0.7) +

geom_vline(xintercept = true_p, color = "red", linetype = "dashed", linewidth = 1) +

facet_wrap(~sample_size_name, scales = "free_y") +

labs(title = "Sampling Distribution of p̂", x = "Sample Allele Frequency (p̂)", y = "Density") +

theme_minimal()