| Concept | Frequentist | Bayesian |

|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Fixed | Random |

| Data | Random | Fixed |

| Estimate | Point estimate | Posterior distribution |

| Confidence Interval | Interval with coverage | Credible interval |

| Hypothesis Test | Reject/Fail to reject | Posterior predictive check |

| P-value | Probability of data under null | Probability of hypothesis given data |

| Likelihood | Function of parameter given data | Function of data given parameter |

Lecture 04: Population Structure and Bayesian Methods in Statistical Genetics

PUBH 8878, Statistical Genetics

Intro to Bayesian Methods

The Bayesian Paradigm

- Let \theta be unknown parameters, y observed data

- While frequentist methods treat \theta as fixed but unknown, Bayesian methods treat \theta as random variables

Sir Thomas Bayes

Bayes’ Theorem

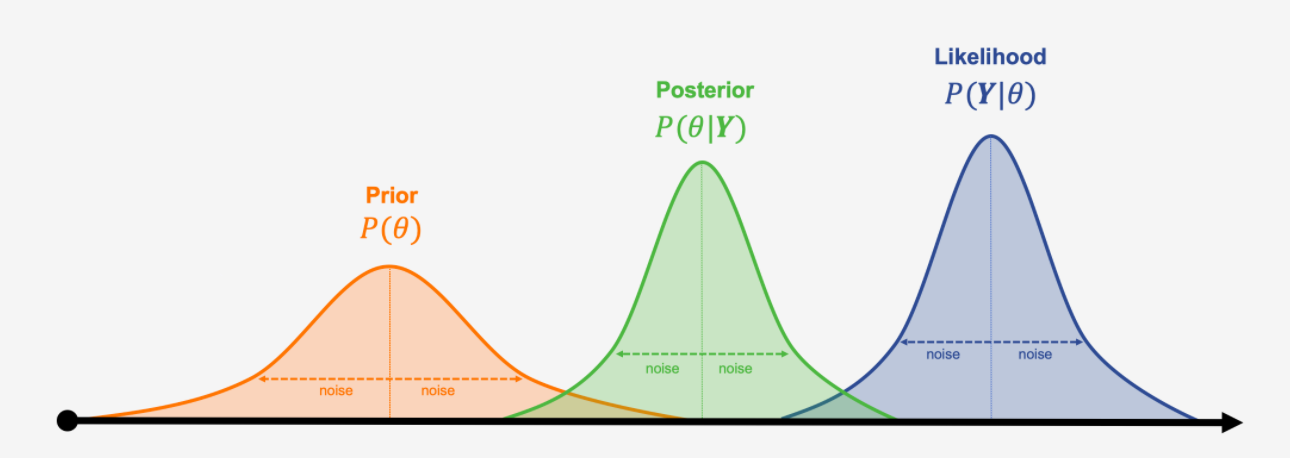

- Uncertainty in \theta is modeled via a prior distribution p(\theta)

- Observed data y are modeled via a likelihood p(y|\theta)

- Bayes’ theorem combines these to yield the posterior distribution p(\theta|y) \propto p(y|\theta)p(\theta)

Frequentist vs Bayesian Terminology

Interpretation of Intervals

Compare statements on intervals

- Frequentist: “Over many repeated samples, 95% of such intervals will contain the true parameter.”

- Bayesian: “Given the observed data and prior, there is a 95% probability that the parameter lies within this interval.”

Bayesian Pros and Cons

Pros

- Intuitive: direct probability statements about parameters

- Flexibility: complex models, hierarchical structures, small-n

- Incorporate prior knowledge or expert opinion

- Full uncertainty quantification via posterior distributions

Cons

- Computationally intensive: MCMC, variational inference

- Sensitivity to prior choice

- Not the status quo in many fields

Further Resources

Conjugacy

- A prior is conjugate to a likelihood if the posterior is in the same family as the prior.

- Example: Beta prior + Binomial likelihood to Beta posterior

Conjugacy Example

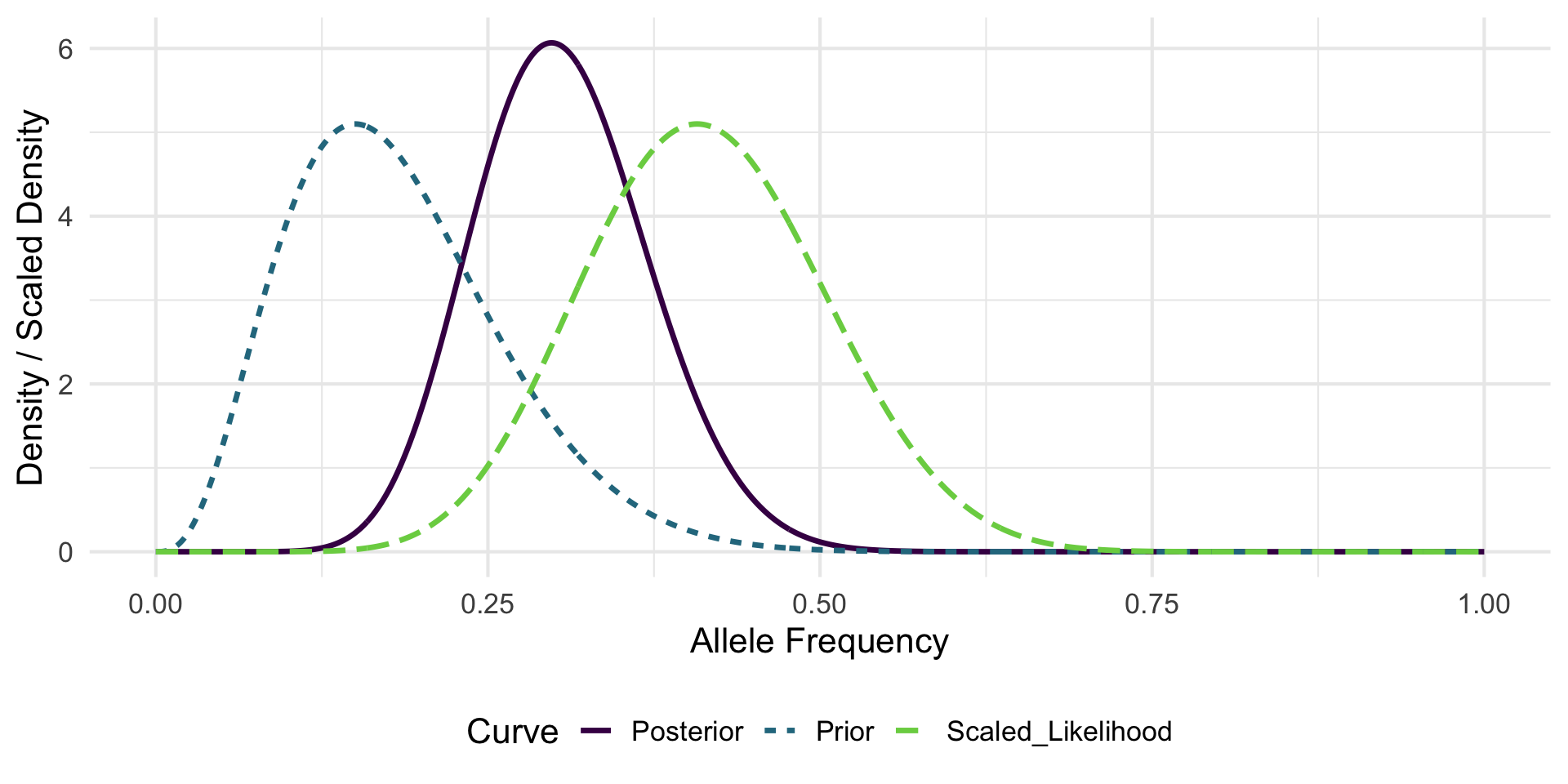

Consider the allele-frequency estimation setup introduced in Lecture 1.

- Previous experiment: observed x_{\text{prev}} = 3 successes (allele A) out of n_{\text{prev}} = 20 trials.

- Current data: x = 11 successes out of n = 27 trials.

- Parameter of interest: allele (“success”) frequency p.

Step 1: Prior

From the previous experiment (3 successes out of 20 trials), we can form a Beta prior:

Interpret \alpha and \beta as pseudo-counts of successes and failures, respectively. (Note that \text{Beta}(1,1) is uniform on 0,1.)

\begin{gather*} p \sim \text{Beta}(\alpha, \beta) \\ \alpha = x_{\text{prev}} + 1 = 4 \\ \beta = n_{\text{prev}} - x_{\text{prev}} + 1 = 18. \end{gather*}

Step 2: Likelihood

Current data likelihood (up to proportionality in p): L(p; x,n) \propto p^{x} (1-p)^{n-x} = p^{11}(1-p)^{16}.

Recognize this kernel as

\text{Beta}(x+1, n-x+1)=\text{Beta}(12,17)

Step 3: Posterior (Conjugacy)

Multiply prior and likelihood kernels: p^{\alpha-1}(1-p)^{\beta-1}\times p^{x}(1-p)^{n-x} = p^{(\alpha + x) - 1}(1-p)^{(\beta + n - x) - 1}.

Thus

\begin{align*} p | x \sim \text{Beta}(\alpha + x,\ \beta + n - x) &= \text{Beta}(4+11,\ 18+16) \\ &= \text{Beta}(15,34). \end{align*}

Posterior Summaries

Posterior mean: E[p|x] = \frac{15}{15+34} = 0.306 (shrinks slightly toward prior mean \frac{4}{22}=0.182 relative to MLE \hat p = 11/27 \approx 0.407).

Effective sample size intuition: prior contributes (\alpha+\beta-2)=20 pseudo-trials; data contribute 27 real trials.

Visualization

Non-Conjugate Models

- Conjugacy is convenient but limited to simple models

- Many realistic models (e.g., multinomial/Dirichlet with nonlinear transforms) are non-conjugate

- Bayesian inference in these models typically requires computational methods like MCMC or variational inference

- Richard McElreath has a great youtube video on MCMC

Bayesian Revisit: ABO Allele Frequencies

- Goal: Infer allele frequencies

(p_A, p_B, p_O)given phenotype counts(n_A, n_AB, n_B, n_O). - Frequentist (Lecture 03): EM treats latent genotypes for A and B phenotypes.

- Bayesian: Place a prior on allele frequencies; integrate (average) over uncertainty rather than impute expected counts.

Data & Sufficient Statistics

- From Lecture 03, we have:

- n_A = 725 individuals with A phenotype

- n_{AB} = 72 individuals with AB phenotype

- n_{B} = 258 individuals with B phenotype

- n_{O} = 1073 individuals with O phenotype

- Total sample size: N = 2128 individuals

Model Specification

- Allele frequency vector: \boldsymbol p=(p_A,p_B,p_O), \boldsymbol p\sim\text{Dirichlet}(\boldsymbol\alpha).

- Under HWE, genotype frequencies: p_A^2, 2p_A p_O, p_B^2, 2 p_B p_O, 2 p_A p_B, p_O^2.

- Phenotype probabilities (aggregating ambiguous genotypes):

- P(\text{A}) = p_A^2 + 2 p_A p_O

- P(\text{AB}) = 2 p_A p_B

- P(\text{B}) = p_B^2 + 2 p_B p_O

- P(\text{O}) = p_O^2

- Likelihood: (n_A,n_{AB},n_B,n_O) \sim \text{Multinomial}(N, \boldsymbol q) with \boldsymbol q above.

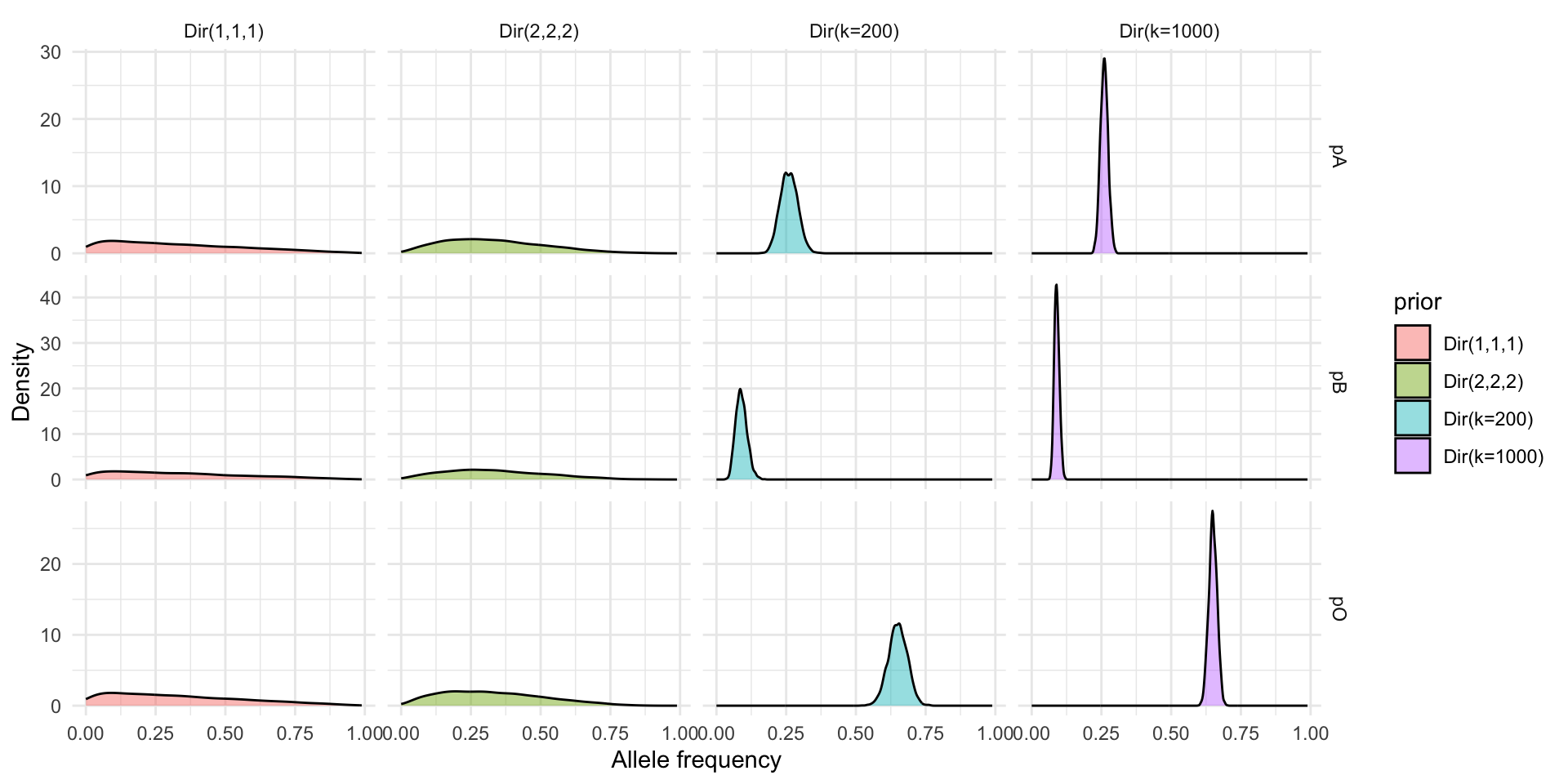

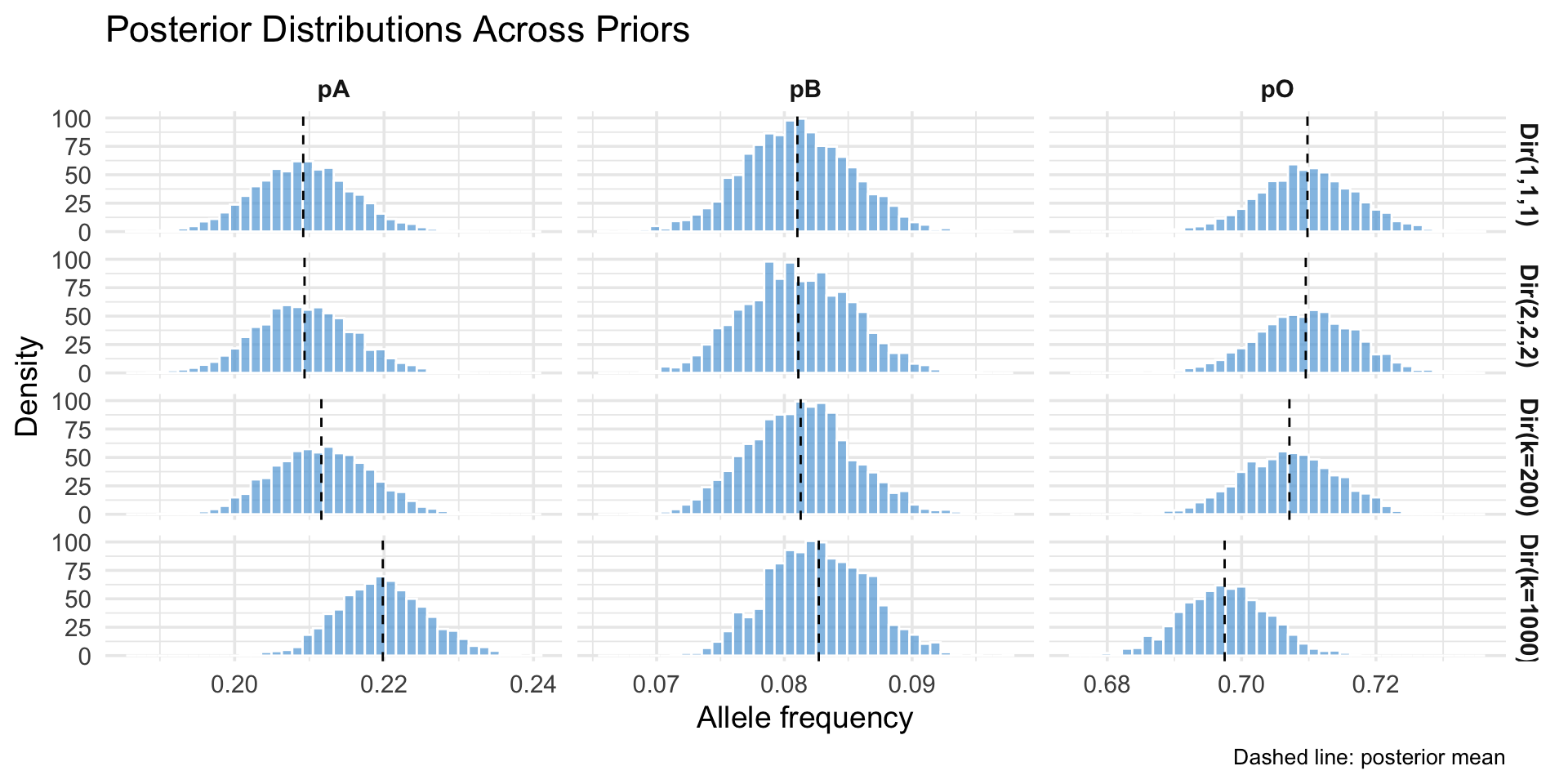

Prior Families

- Weak Dirichlet(1,1,1) (uniform over allele simplex)

- Mild Dirichlet(2,2,2) (light shrink toward center)

Using Historical Data

- Consider global survey means (p_A = 0.26, p_B = 0.09, p_O = 0.65) (Mourant et al., 1976; Yamamoto et al., 2012).

- Dirichlet prior: \mathbf{\alpha} = k (0.26, 0.09, 0.65)

- Effective sample size idea: acts like observing k allele draws before current data (2N alleles in sample).

- Relative weight vs data (here total alleles = 2N = 4256):

- k = 200 \to prior weight \approx 4.5\% of total information.

- k = 1000 \to prior weight \approx 19.0\% of total information.

Prior Shapes (Marginal Densities)

How to fit these models?

- So we have our data, likelihood, and priors

- We can use MCMC to sample from the posterior distribution of allele frequencies

- There exist many software packages to do this! We will use Stan (Carpenter et al., 2017) via the

cmdstanrR package

Stan Model

Step 1: Phenotype Probabilities

- 1

-

Declare the

functionsblock (optional in Stan, but lets us encapsulate logic) - 2

- Define a helper that maps allele frequencies to phenotype probabilities

- 3

- Extract components (for readability in later expressions)

Stan Model

Step 1: Phenotype Probabilities

- 4

-

Allocate a length-4 vector

q(A, AB, B, O) for phenotype probabilities - 5

- Hardy–Weinberg genotype algebra aggregated into phenotype probabilities

- 6

- Return the vector

Stan Model

Step 2: Data & Transforms

- 1

-

Raw observed counts and prior hyperparameters enter in the

datablock. - 2

- ABO phenotype counts (non-negative integers) per category.

- 3

-

Dirichlet prior parameters supplied from R (allow different priors via

alpha).

Stan Model

Step 2: Data & Transforms

- 4

-

transformed datapre-computes deterministic quantities once - 5

- Total sample size N used for reference or diagnostics

- 6

- Assemble counts into an array to pass to the multinomial

Stan Model

Step 3: Parameters & Derived q

- 1

-

Declare unknown quantities to infer in

parameters - 2

-

simplex[3]enforces positivity and sum-to-one constraints automatically - 3

-

transformed parametersrecomputes per-draw derived values - 4

- Reuse helper to obtain phenotype probabilities from allele frequencies

Stan Model (Step 4: Prior & Likelihood)

- 1

-

The

modelblock contains all sampling statements contributing to log density - 2

-

Dirichlet prior on allele frequencies

p - 3

-

Multinomial likelihood over phenotype counts with probabilities

q.

Stan Model (Step 5: Generated Quantities)

1generated quantities {

2 real log_lik = multinomial_lpmf(y | q);

3 vector[6] geno_freq;

4 real pA = p[1]; real pB = p[2]; real pO = p[3];

5 geno_freq[1] = pA * pA; # AA

geno_freq[2] = 2 * pA * pO; # AO

geno_freq[3] = pB * pB; # BB

geno_freq[4] = 2 * pB * pO; # BO

geno_freq[5] = 2 * pA * pB; # AB

geno_freq[6] = pO * pO; # OO

}- 1

- Post-processing: quantities saved per posterior draw

- 2

- Store log-likelihood for model comparison / LOO / WAIC

- 3

- Allocate genotype frequency vector

- 4

- Local aliases improve clarity when computing genotype frequencies

- 5

- Hardy–Weinberg genotype probabilities

Compile Stan Model

- Stan uses C++ on the backend, so we need to compile the model once before fitting

cmdstan_model()handles compilation and returns a model object for sampling

Fit: Weak Prior (Dirichlet(1,1,1))

- 1

-

Execute the MCMC sampler using the

sample()method on the compiled model object - 2

- Pass data from R to Stan as a named list

- 3

- Specify MCMC sampler settings

Running MCMC with 4 parallel chains...

Chain 1 finished in 0.0 seconds.

Chain 2 finished in 0.0 seconds.

Chain 3 finished in 0.0 seconds.

Chain 4 finished in 0.0 seconds.

All 4 chains finished successfully.

Mean chain execution time: 0.0 seconds.

Total execution time: 0.2 seconds.Model Diagnostics

# A tibble: 18 × 10

variable mean median sd mad q5 q95 rhat ess_bulk

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 lp__ -2.31e+3 -2.31e+3 9.83e-1 7.26e-1 -2.31e+3 -2.31e+3 1.00 1880.

2 p[1] 2.09e-1 2.09e-1 6.60e-3 6.52e-3 1.99e-1 2.20e-1 1.00 4495.

3 p[2] 8.10e-2 8.09e-2 4.23e-3 4.26e-3 7.41e-2 8.81e-2 1.00 2125.

4 p[3] 7.10e-1 7.10e-1 7.27e-3 7.18e-3 6.98e-1 7.22e-1 1.00 3368.

5 q[1] 3.41e-1 3.41e-1 9.80e-3 9.84e-3 3.25e-1 3.57e-1 1.00 4376.

6 q[2] 3.39e-2 3.39e-2 1.92e-3 1.92e-3 3.08e-2 3.70e-2 1.00 2338.

7 q[3] 1.22e-1 1.21e-1 6.27e-3 6.21e-3 1.11e-1 1.32e-1 1.00 2210.

8 q[4] 5.04e-1 5.04e-1 1.03e-2 1.02e-2 4.87e-1 5.21e-1 1.00 3368.

9 log_lik -1.16e+1 -1.13e+1 9.81e-1 7.14e-1 -1.36e+1 -1.07e+1 1.00 1867.

10 geno_freq… 4.38e-2 4.37e-2 2.76e-3 2.73e-3 3.94e-2 4.85e-2 1.00 4495.

11 geno_freq… 2.97e-1 2.97e-1 7.10e-3 7.08e-3 2.85e-1 3.08e-1 1.00 4242.

12 geno_freq… 6.58e-3 6.55e-3 6.87e-4 6.90e-4 5.50e-3 7.76e-3 1.00 2125.

13 geno_freq… 1.15e-1 1.15e-1 5.59e-3 5.53e-3 1.06e-1 1.24e-1 1.00 2225.

14 geno_freq… 3.39e-2 3.39e-2 1.92e-3 1.92e-3 3.08e-2 3.70e-2 1.00 2338.

15 geno_freq… 5.04e-1 5.04e-1 1.03e-2 1.02e-2 4.87e-1 5.21e-1 1.00 3368.

16 pA 2.09e-1 2.09e-1 6.60e-3 6.52e-3 1.99e-1 2.20e-1 1.00 4495.

17 pB 8.10e-2 8.09e-2 4.23e-3 4.26e-3 7.41e-2 8.81e-2 1.00 2125.

18 pO 7.10e-1 7.10e-1 7.27e-3 7.18e-3 6.98e-1 7.22e-1 1.00 3368.

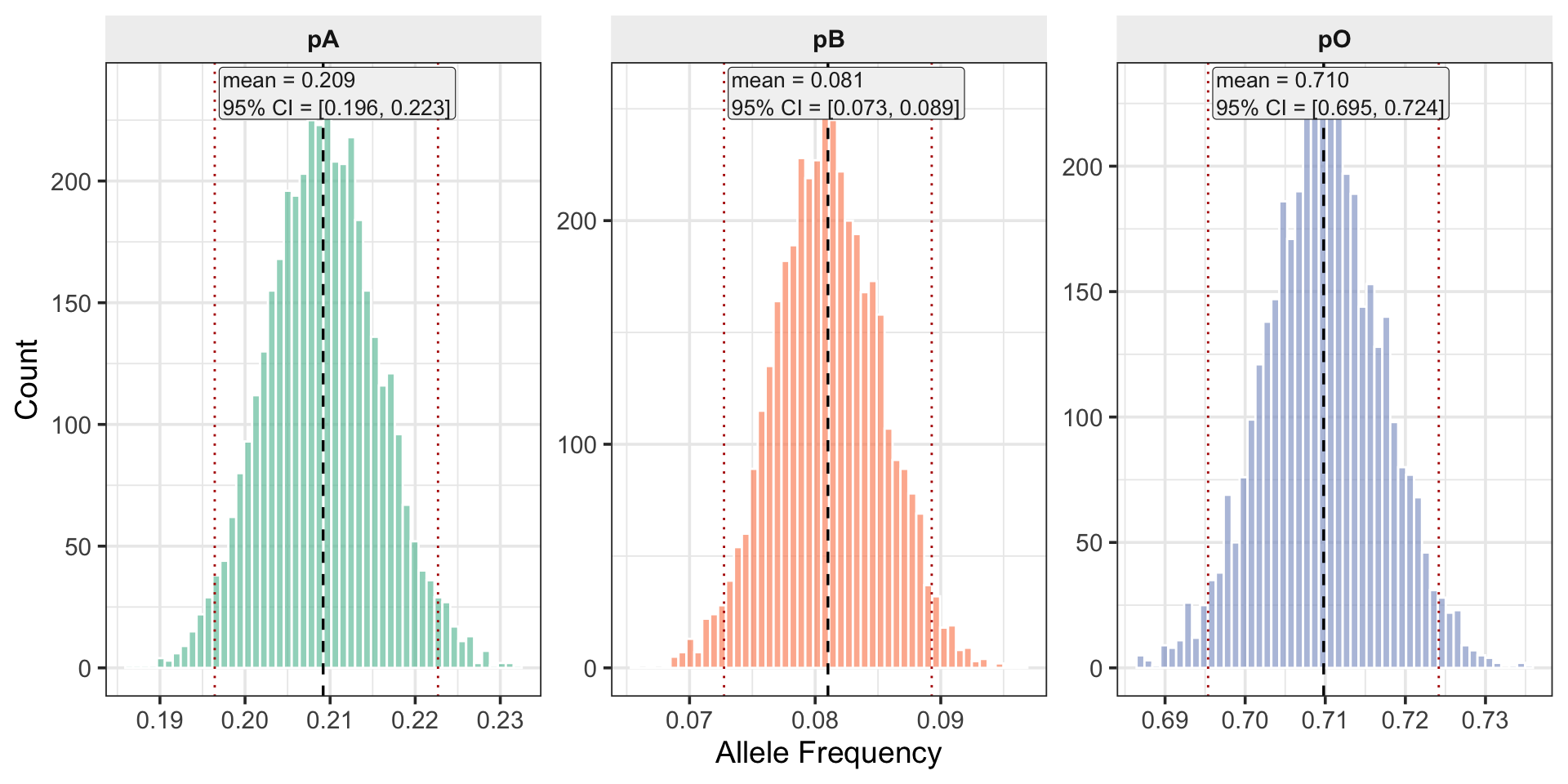

# ℹ 1 more variable: ess_tail <dbl>Posterior Summaries & Intervals (Weak Prior)

post_weak <- fit_weak$draws(variables = c("p")) |> as_draws_df()

weak_summ <- post_weak %>% summarise(

mean_pA = mean(`p[1]`), mean_pB = mean(`p[2]`), mean_pO = mean(`p[3]`),

sd_pA = sd(`p[1]`), sd_pB = sd(`p[2]`), sd_pO = sd(`p[3]`)

)

weak_ci <- post_weak %>% summarise(

pA_low = quantile(`p[1]`, 0.025), pA_high = quantile(`p[1]`, 0.975),

pB_low = quantile(`p[2]`, 0.025), pB_high = quantile(`p[2]`, 0.975),

pO_low = quantile(`p[3]`, 0.025), pO_high = quantile(`p[3]`, 0.975)

)Posterior Histograms (Weak Prior)

EM vs Bayesian Point Estimates

# A tibble: 2 × 5

method pA pB pO loglik

<chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

1 EM 0.209 0.0808 0.710 -2304.

2 Posterior Mean 0.209 0.0810 0.710 NA Consolidated Posterior Comparison

Population Structure

Population Substructure

- Features of a population which result from variation of expected allele frequencies across individuals

- Standard allele counting (\hat{p} = (2n_{AA} + n_{Aa}/2n)) will still be unbiased

- But, not all subjects may have the same probability of being represented in the sample

- Variance of estimate will be effected

Population Stratification

- Individuals in a population can be subdivided into mutually exclusive strata

- Within each strata the allele frequency is the same for all individuals

- Intuitively, we are partitioning a large dataset into multiple smaller datasets

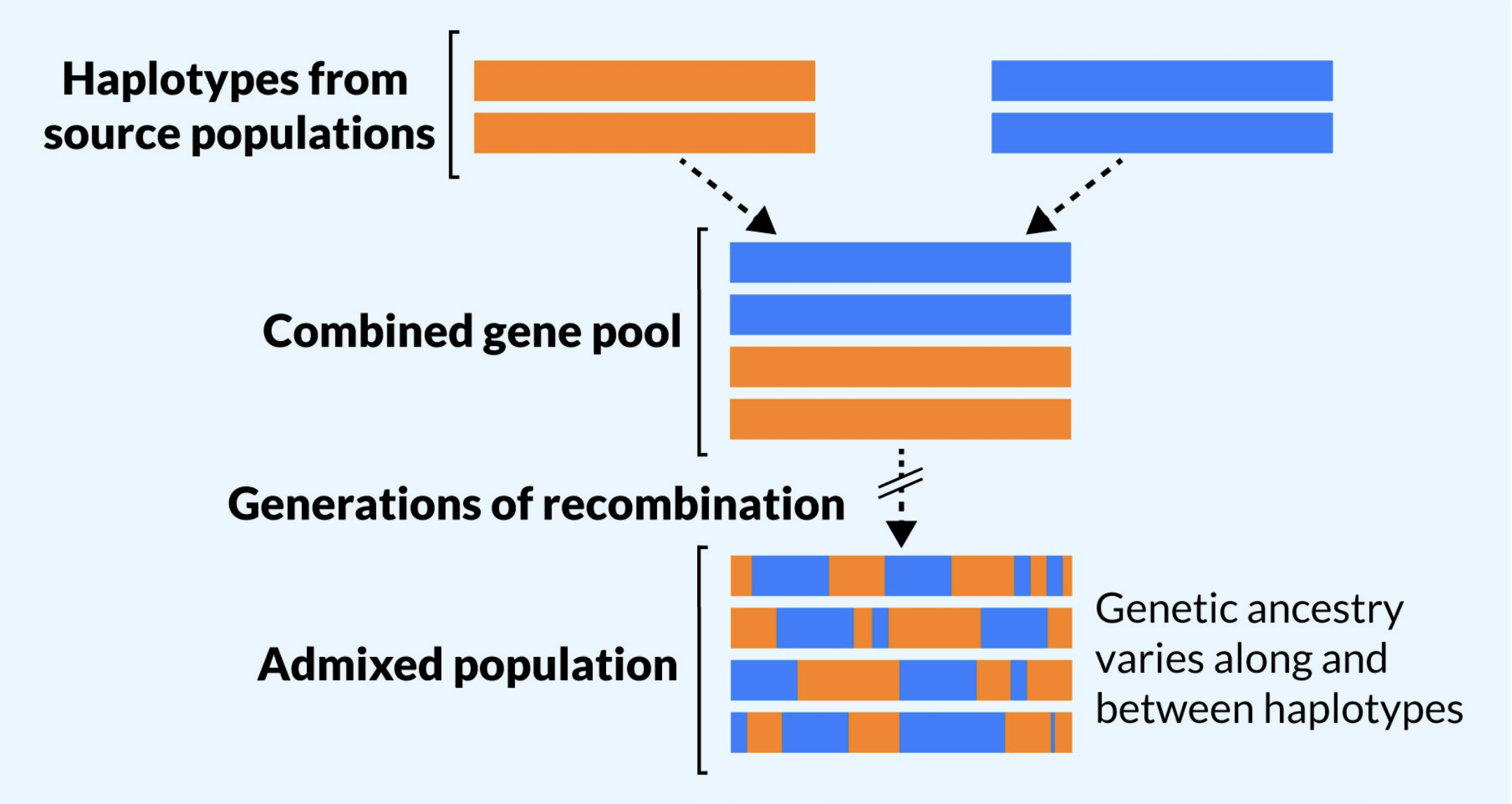

Population Admixture

- When individuals in a population have a mixture of different genetic ancestries due to prior mixing of two or more populations

- Often result of migration

Population Admixture

From Korunes and Goldberg (2021)

Population Inbreeding

- Occurs when there is a preference for mating among relatives in a population or because geographic isolation of subgroups restricts mating choices

- Possibility that an offspring will inherit two copies of the same ancestral allele

- Define F, the inbreeding coefficient, as the probability that a random individual in the population inherits two copies of the same allele from a common ancestor

Admixture as a Confounder

- Consider the problem of estimating the effect of a SNP on a disease phenotype: \beta in P(Y=1) = \text{logit}^{-1}(\alpha + \beta G)

- Recent admixture mixes ancestries within individuals: genotype is a convex combination of source populations

- If phenotype prevalence differs by ancestry, local or global ancestry proportions act like hidden covariates

- Association tests must separate causal signal from ancestry-driven allele frequency differences

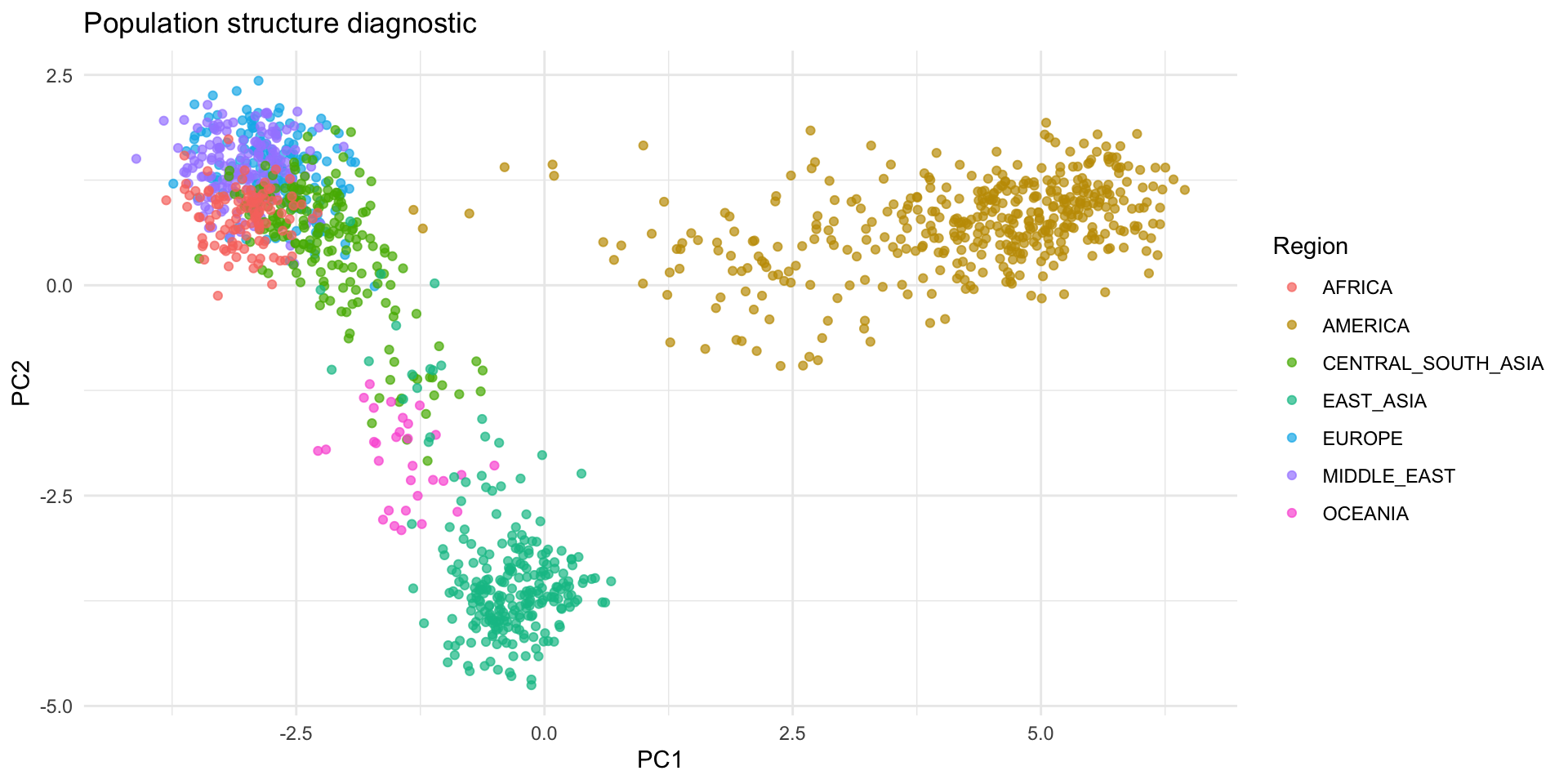

Principal Components for Structure

- Construct the standardized genotype matrix Z and compute Z^T Z / M (with M markers)

- Top eigenvectors capture major ancestry gradients

- Use the leading PCs as covariates in association tests or to stratify downstream analyses

Principal Components for Structure

/// GENIND OBJECT /////////

// 1,350 individuals; 678 loci; 8,170 alleles; size: 44.1 Mb

// Basic content

@tab: 1350 x 8170 matrix of allele counts

@loc.n.all: number of alleles per locus (range: 5-35)

@loc.fac: locus factor for the 8170 columns of @tab

@all.names: list of allele names for each locus

@ploidy: ploidy of each individual (range: 2-2)

@type: codom

@call: read.fstat(file = file, missing = missing, quiet = quiet)

// Optional content

@pop: population of each individual (group size range: 3-50)

@other: a list containing: popInfo Principal Components for Structure

hgdp_df <- genind2df(eHGDP, sep = "/")

# Convert to allele count matrix, center columns (replace missing with locus means)

geno_mat <- scaleGen(eHGDP, center = TRUE, scale = FALSE, NA.method = "mean")

pc_fit <- prcomp(geno_mat, center = FALSE, scale. = FALSE)

# Map individuals to geographic regions for coloring

pop_info <- eHGDP@other$popInfo

pop_index <- as.integer(pop(eHGDP))

region <- pop_info$Region[pop_index]

plot_df <- data.frame(PC1 = pc_fit$x[, 1], PC2 = pc_fit$x[, 2], Region = region)

ggplot(plot_df, aes(PC1, PC2, color = Region)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.7, size = 1.5) +

labs(title = "Population structure diagnostic", x = "PC1", y = "PC2") +

theme_minimal()Principal Components for Structure

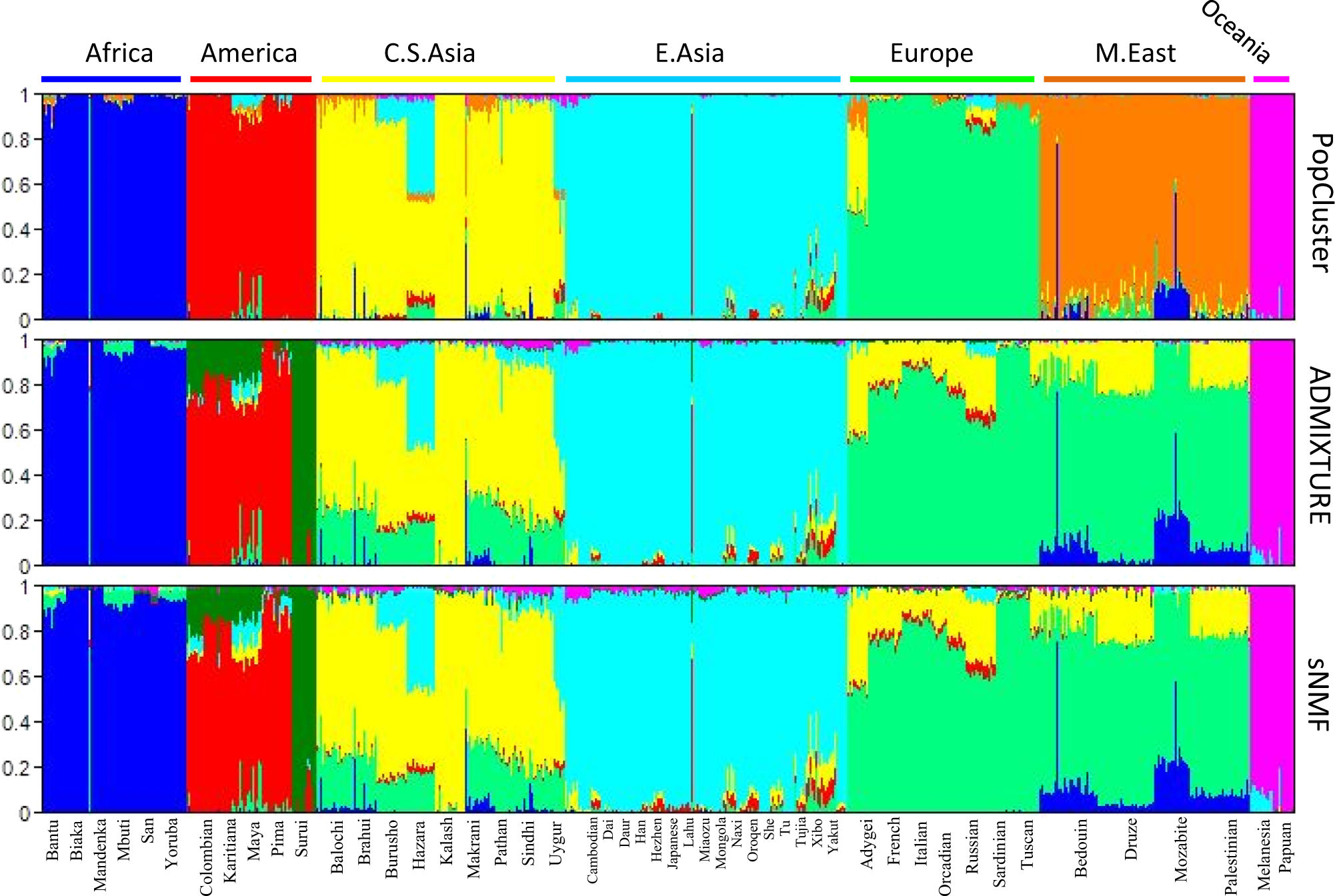

STRUCTURE & ADMIXTURE

- Model-based clustering methods for population structure inference

- Assume K latent populations with distinct allele frequencies

- Each individual has ancestry proportions \boldsymbol{\pi}_i across K populations

- Each genotype is drawn from a mixture of population-specific allele frequencies

- Use maximum likelihood (ADMIXTURE) or Bayesian inference (STRUCTURE) to estimate parameters

Assumptions

- Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium within each ancestral population

- Linkage equilibrium between loci within each ancestral population

- Loci are unlinked (or weakly linked)

Example Output

Bayesian Admixture

- Latent populations k = 1,\ldots,K possess allele frequencies \theta_{k\ell} at locus \ell

- Individual ancestry proportions \boldsymbol{\pi}_i \sim \text{Dirichlet}(\boldsymbol{\alpha})

- Genotype y_{i\ell} \sim \text{Binomial}\left(2, \sum_{k} \pi_{ik} \theta_{k\ell}\right) assuming HWE within each ancestral population

- Posterior draws propagate ancestry/allele-frequency uncertainty into association testing, local ancestry, and polygenic prediction

Identifiability & Label Switching

- Problem: Mixture components are exchangeable → posterior multimodality

- Solution: Anchor loci with informative priors break symmetry

- Populations defined by genetic signatures, not arbitrary labels

- Multiple anchors provide robustness against weak signals

Stan Model: Data & Parameters

data {

int<lower=1> N; // individuals

int<lower=1> L; // loci

int<lower=1> K; // ancestral pops

array[N, L] int<lower=0, upper=2> y; // genotypes (0,1,2)

int<lower=0> L_soft;

array[L_soft] int<lower=1, upper=L> soft_idx; // e.g., {2}

array[K] real<lower=0> a_theta; // Beta 'a' for non-anchor loci

array[K] real<lower=0> b_theta; // Beta 'b' for non-anchor loci

int<lower=1, upper=L> l_star; // anchor locus index

real<lower=0> conc_pi; // shared Dirichlet conc. for pi

}Stan Model: Parameters & Transformed Parameters

parameters {

array[N] simplex[K] pi; // ancestry proportions

ordered[K] eta; // ordered logits at anchor locus

matrix<lower=0, upper=1>[K, L-1] theta_rest; // allele freqs for non-anchor loci

}

transformed parameters {

matrix<lower=0, upper=1>[K, L] theta; // full allele-frequency matrix

matrix[N, L] p_mix; // mixed allele frequency

// anchor column (ordered)

for (k in 1:K) theta[k, l_star] = inv_logit(eta[k]);

// fill remaining columns

{

int c = 1;

for (l in 1:L) {

if (l == l_star) continue;

for (k in 1:K) theta[k, l] = theta_rest[k, c];

c += 1;

}

}

// mixture expectations

for (n in 1:N)

for (l in 1:L)

p_mix[n, l] = dot_product(pi[n], col(theta, l));

}Stan Model: Priors & Likelihood

model {

// priors

eta ~ normal(0, 2.5); // weak prior; ordering gives ID

for (k in 1:K)

for (c in 1:(L - 1))

theta_rest[k, c] ~ beta(a_theta[k], b_theta[k]);

for (n in 1:N)

pi[n] ~ dirichlet(rep_vector(conc_pi, K));

for (c in 1:L_soft) {

int l = soft_idx[c];

if (l != l_star) {

// comp 1 LOW, comp 2 HIGH at these loci (gentle)

target += beta_lpdf(theta[1, l] | 2, 8);

target += beta_lpdf(theta[2, l] | 8, 2);

}

}

// likelihood

for (n in 1:N)

for (l in 1:L)

y[n, l] ~ binomial(2, p_mix[n, l]);

}Stan Model: Generated Quantities

Mathematical Framework

Individual-Locus Allele Frequency

For individual i at locus \ell, expected allele frequency: p_{i\ell} = \sum_{k=1}^K \pi_{ik} \theta_{k\ell}

Information Borrowing Across Loci

Key insight: Same \boldsymbol{\pi}_i parameters appear in likelihood for all loci

L(\boldsymbol{\pi}_i, \boldsymbol{\Theta}) = \prod_{\ell=1}^L \text{Binomial}\left(y_{i\ell} \mid 2, \sum_{k=1}^K \pi_{ik} \theta_{k\ell}\right)

Mathematical Framework

Hierarchical Learning

- Anchor loci provide strong identification signal

- Remaining loci contribute cumulative evidence

- Posterior uncertainty propagates through all parameters

Simulating Admixed Genotypes

- 1

- Fixed random seed for consistent results across sessions

- 2

- Normalized gamma variates generate simplex-constrained ancestry proportions

- 3

- Set simulation parameters

Simulating Admixed Genotypes

4# Create very clear population differentiation

theta_true <- matrix(0, nrow = K, ncol = L)

# Multiple anchor loci: very strong differentiation

theta_true[1, 1] <- 0.1 # Pop 1: very low frequency at anchor 1

theta_true[2, 1] <- 0.9 # Pop 2: very high frequency at anchor 1

theta_true[1, 2] <- 0.1 # Pop 1: very low frequency at anchor 2

theta_true[2, 2] <- 0.9 # Pop 2: very high frequency at anchor 2

# Other loci: strong differentiation

theta_true[1, 3:L] <- rbeta(L-2, 2, 8) # Pop 1: much lower overall

theta_true[2, 3:L] <- rbeta(L-2, 8, 2) # Pop 2: much higher overall

5pi_true <- rbind(

rdirichlet(12, c(90, 10)), # pop 1

rdirichlet(12, c(10, 90)), # Very pure pop 2

rdirichlet(16, c(10, 10)) # Admixed individuals

)- 4

- Strong genetic signatures with multiple anchor loci

- 5

- Mix of unadmixed founders and admixed descendants

Simulating Admixed Genotypes

6y <- matrix(0L, nrow = N, ncol = L)

for (n in 1:N) {

for (l in 1:L) {

p_mix <- sum(pi_true[n, ] * theta_true[, l])

y[n, l] <- rbinom(1, size = 2, prob = p_mix)

}

}- 6

- Genotypes drawn from Binomial(2, p_mix) per individual and locus

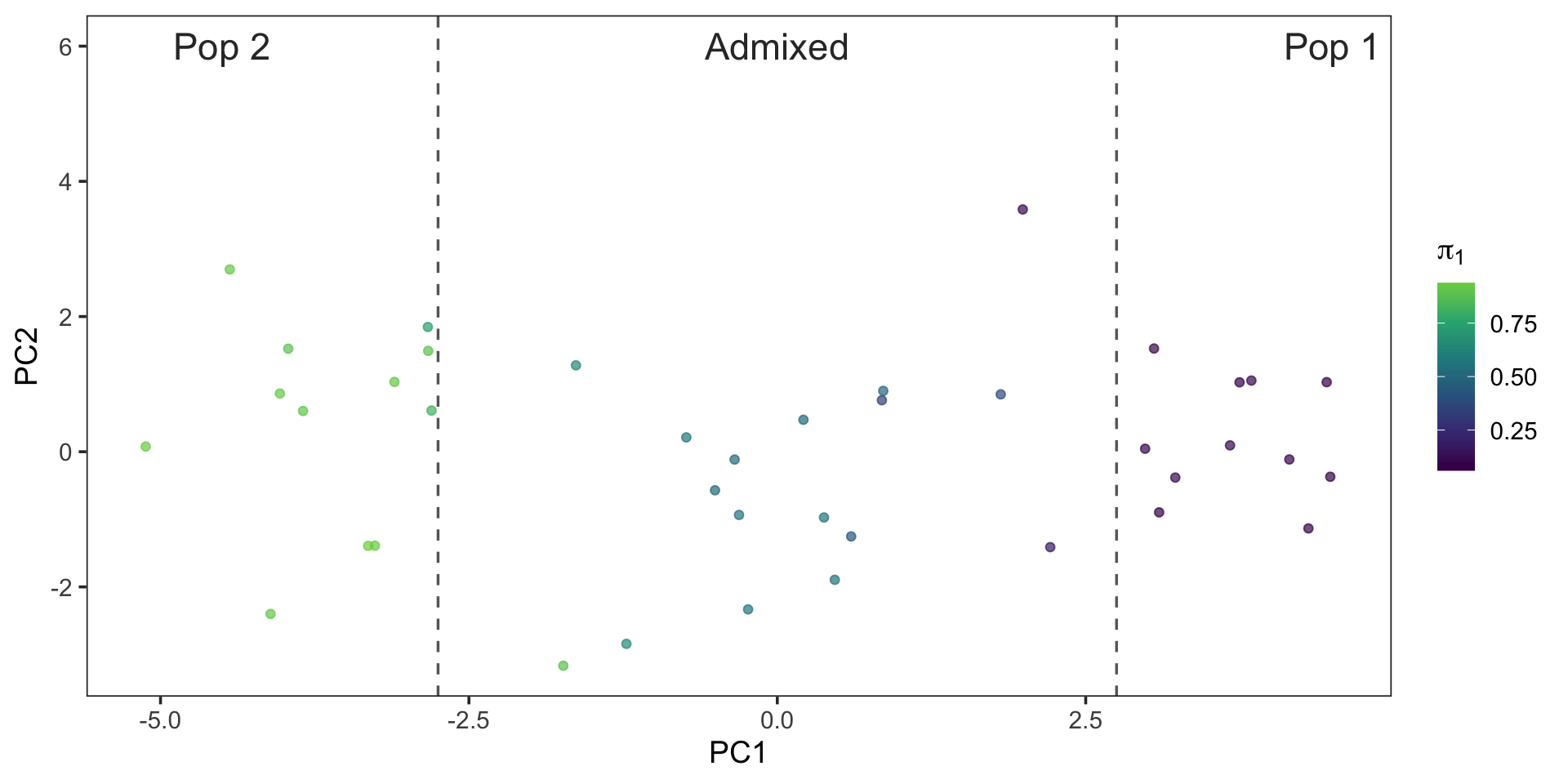

PCA On Simulated Genotypes

- Center genotypes by 2 \times \hat{p} and scale by \sqrt{2 \cdot \hat{p} \cdot (1 - \hat{p})}

p_hat <- colMeans(y) / 2

sd_hat <- sqrt(pmax(1e-6, 2 * p_hat * (1 - p_hat)))

Z <- scale(y, center = 2 * p_hat, scale = sd_hat)

pc <- prcomp(Z, center = FALSE, scale. = FALSE)

pc_df <- data.frame(PC1 = pc$x[, 1], PC2 = pc$x[, 2], pi1 = pi_true[, 1])

ggplot(pc_df, aes(PC1, PC2, color = pi1)) +

geom_point(alpha = 0.7, size = 1.6) +

scale_color_viridis_c(end = .8) +

labs(color = expression(pi[1]), x = "PC1", y = "PC2") +

geom_vline(xintercept = 2.75, linetype = "dashed", color = "gray40", linewidth = 0.6) +

geom_vline(xintercept = -2.75, linetype = "dashed", color = "gray40", linewidth = 0.6) +

annotate("text", x = 4.5, y = 6, label = "Pop 1", color = "gray20", size = 6) +

annotate("text", x = -4.5, y = 6, label = "Pop 2", color = "gray20", size = 6) +

annotate("text", x = 0, y = 6, label = "Admixed", color = "gray20", size = 6) +

theme_bw(base_size = 14) +

theme(panel.grid = element_blank()) PCA On Simulated Genotypes

Fitting the Model

admix_mod <- cmdstan_model(file.path("stan", "structure_admixture.stan"))

l_star <- 1 # choose your anchor locus (e.g., 1)

admix_data <- list(

N = N, L = L, K = K, y = y,

a_theta = rep(1.5, K), b_theta = rep(1.5, K),

l_star = l_star, L_soft = 1, soft_idx = c(2),

conc_pi = 2.0

)

admix_fit <- admix_mod$sample(

data = admix_data,

chains = 4, parallel_chains = 4,

iter_warmup = 2000, iter_sampling = 2000,

seed = 887804, refresh = 0

)Running MCMC with 4 parallel chains...Chain 2 Informational Message: The current Metropolis proposal is about to be rejected because of the following issue:Chain 2 Exception: binomial_lpmf: Probability parameter is 1, but must be in the interval [0, 1] (in '/var/folders/3f/7lk7ddbn19j4f1rzxtlx3z9w0000gn/T/RtmpX9Wapd/model-d8207aefdca0.stan', line 65, column 6 to column 41)Chain 2 If this warning occurs sporadically, such as for highly constrained variable types like covariance matrices, then the sampler is fine,Chain 2 but if this warning occurs often then your model may be either severely ill-conditioned or misspecified.Chain 2 Chain 4 Informational Message: The current Metropolis proposal is about to be rejected because of the following issue:Chain 4 Exception: binomial_lpmf: Probability parameter is 1, but must be in the interval [0, 1] (in '/var/folders/3f/7lk7ddbn19j4f1rzxtlx3z9w0000gn/T/RtmpX9Wapd/model-d8207aefdca0.stan', line 65, column 6 to column 41)Chain 4 If this warning occurs sporadically, such as for highly constrained variable types like covariance matrices, then the sampler is fine,Chain 4 but if this warning occurs often then your model may be either severely ill-conditioned or misspecified.Chain 4 Chain 2 finished in 8.6 seconds.

Chain 1 finished in 8.7 seconds.

Chain 4 finished in 8.6 seconds.

Chain 3 finished in 9.0 seconds.

All 4 chains finished successfully.

Mean chain execution time: 8.7 seconds.

Total execution time: 9.1 seconds.Stan Output

dm <- admix_fit$draws(variables = c("theta","pi"), format = "draws_df")

lstar <- admix_data$l_star

L <- ncol(y)

non_anchor <- setdiff(1:L, lstar)

# Orientation score per draw: average sign over non-anchor loci

sign_per_draw <- rowMeans(sapply(non_anchor, function(l)

sign(dm[[sprintf("theta[2,%d]", l)]] - dm[[sprintf("theta[1,%d]", l)]])))

# Reference orientation: the majority sign across all draws

ref_sign <- ifelse(mean(sign_per_draw) >= 0, -1, 1)

# Decide which DRAWS to flip (not just which chains)

flip_draw <- sign_per_draw * ref_sign < 0

# Helper: swap theta rows and pi columns for those draws

swap_block <- function(df, pat1, pat2, idx){

i1 <- grep(pat1, names(df)); i2 <- grep(pat2, names(df))

tmp <- df[idx, i1, drop=FALSE]

df[idx, i1] <- df[idx, i2, drop=FALSE]

df[idx, i2] <- tmp

df

}

# Swap theta rows

dm <- swap_block(dm, "^theta\\[1,", "^theta\\[2,", flip_draw)

# Swap pi columns

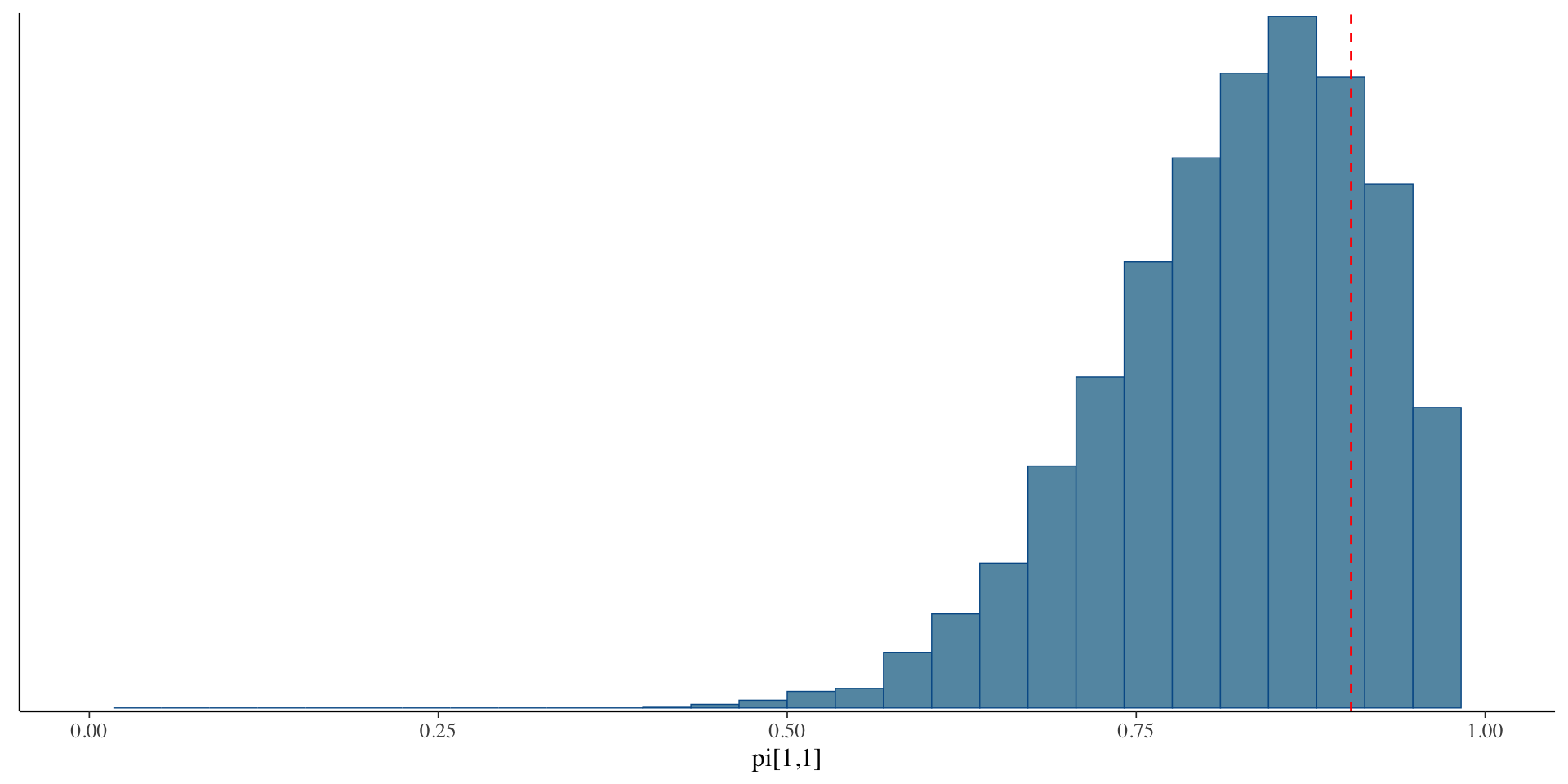

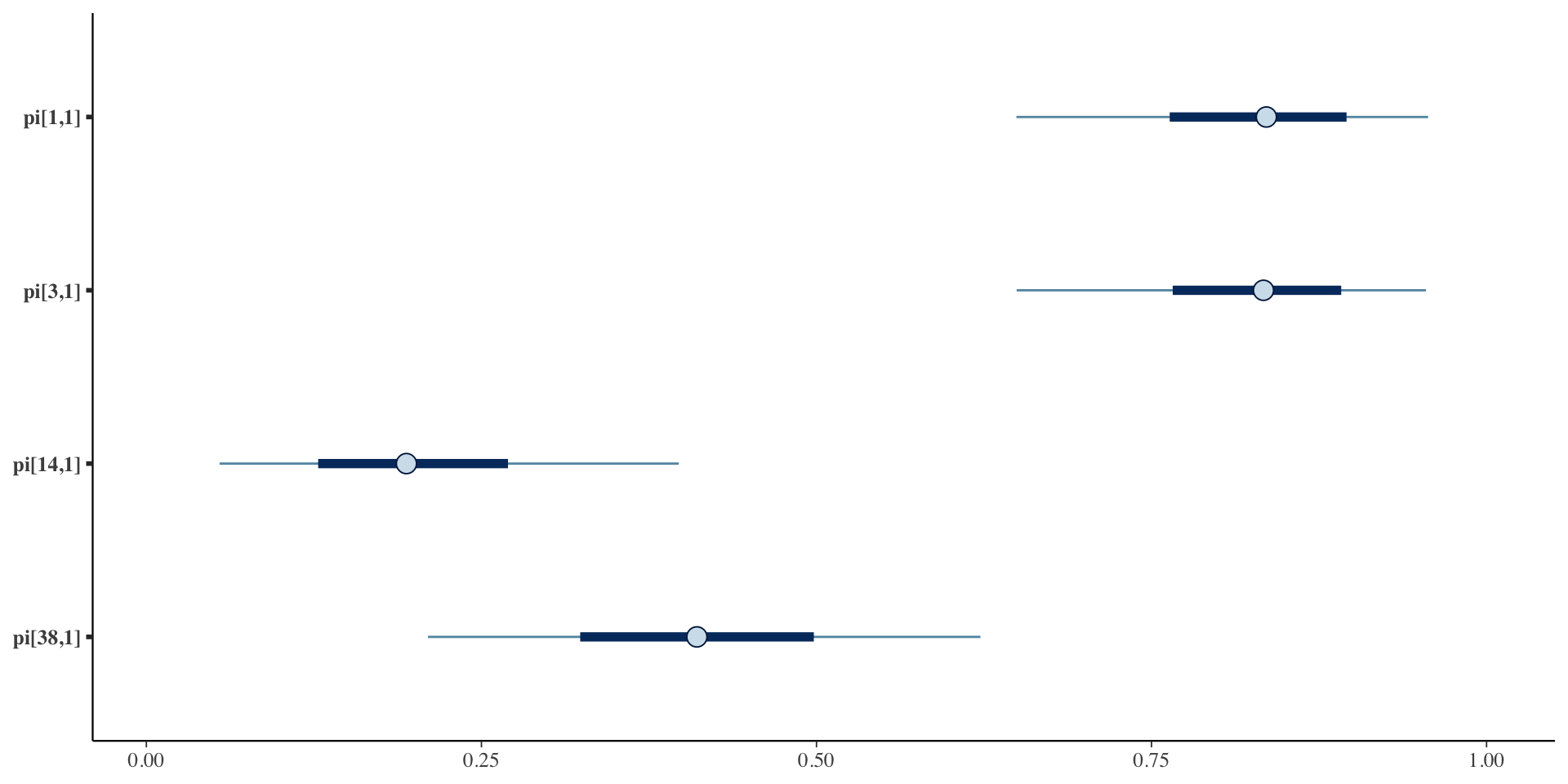

dm <- swap_block(dm, "^pi\\[[0-9]+,1\\]$", "^pi\\[[0-9]+,2\\]$", flip_draw)Aligned Posteriors

Credible Intervals

Summary & Next Steps

- Population structure influences genetic analyses

- Bayesian framing exposes prior choices, enables posterior uncertainty on structure (ABO example, admixture Stan model)

- Bayesian modeling as attempting to capture the data-generating process